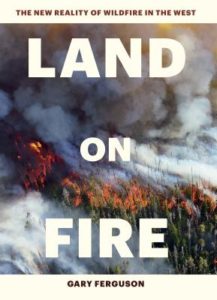

“Land on Fire: The New Reality of Wildfire in the West” is a new book by writer Gary Ferguson in which the subject of wildfire and Western land is discussed in great detail. This book is something of a departure for Ferguson, who has previously written several wonderful, personal books about his experiences and observations in the American West.

“Land on Fire: The New Reality of Wildfire in the West” is a new book by writer Gary Ferguson in which the subject of wildfire and Western land is discussed in great detail. This book is something of a departure for Ferguson, who has previously written several wonderful, personal books about his experiences and observations in the American West.

This book trades his usual poetic treatment for a more informational, educational approach and sheds light on questions now being asked about our ability to better manage lands with a greater appreciation for and acceptance of wildfire.

The natural history of the American West can be read in all the varied, majestic landscapes that have captured imaginations for centuries. It’s a history written by the elements of wind, water and fire on an incredible geologic canvas.

We humans have been successful largely because of an ability to insert ourselves into natural processes where elements interact with the land. The very basis of human civilization stems from our ability to control the relationship of water and land for agriculture. The winds have filled our sails and pushed us to become seafarers, fishermen, explorers and conquerors, to say nothing of the capture of wind energy to mill grain and more recently generate electricity, cleanly powering our civilization.

Beyond its controlled use for heat, cooking and controlled combustion, fire has largely been embraced for its powers of destruction, and much of the history of Euro-humans and wildfire focuses on our efforts to contain and suppress its destructive force.

The lack of fire in the American West in the last century is now a significant factor in the future potential for fire, as policies of fire suppression have been one of the most persistent in our national land management policy portfolio. It is critical to state that fire has always played a destructive role. The fire season of 1910, like the season of 1889, burned extensive areas with incredible ferocity, and these fires predated policies of widespread suppression.

To insinuate that fire was not a destructive force before 1910 is historically incorrect. However, fire usually played a much more measured role in our forests, burning more often and less intensely, cleaning the forest of bio-debris and fuels, enriching soils, and strengthening the forest as habitat for a great variety of plants and animals. The fire season of 1910, which has since been known as the “Big Burn” because it consumed 3 million acres of forest in the Northern Rockies, was a turning point in American wildfire policy that set us on an expensive and sisyphean path to try to protect forested lands from the destructive force of wildfire.

Because we’ve not let fires burn, it is now a fact that there is an accumulation of fuel in the forests.

America’s forests are thus primed for burning and the repercussions of those fires could make future forest management more challenging. So-called “mega-fires” which consume larger areas of forest (usually burn areas in excess of 100,000 acres) but which also are more destructive of the areas burned are increasingly common. Forests in the aftermath of big, intense burns are showing signs of failure to re-seed, and there is evidence to suggest that some forests recovering from these large destructive fires are more prone to be replaced by monocultures (forests of largely a single species) than the forest that existed before the burn. These monoculture forests are less resilient to beetles and pathogens, and other factors that accelerate the production of fuel.

Ferguson states in his book: “There have been four years in the last half century when more than 9 million acres have burned in the United States, and all of them have been since 2006.” (p. 24) They are boosted by the accumulation of fuels, at a time when climate change is driving hotter, drier conditions into the forests. The success of species like the pine bark beetle, which in recent decades have found more stressed forests where they can thrive, has further stressed forest ecosystems and added additional fuel.

The complex conditions that govern wildfire have been at work in western forests going back long before Europeans arrived, but they have been amplified in recent decades. The most significant factor is the explosive growth of human activity, particularly low-density rural housing. The term used to describe the area where human structures and wildland fuels overlap is WUI, or wildland-urban interface. In the United States today (Ferguson provides only a national figure, not one specific to the West), about 1 billion acres of a total 2.3 billion acres of land are considered WUI. That’s roughly 44 percent of the country. Much of that area, particularly in the West, has conditions ripe for wildfire.

The increased area of wildland-urban interface not only means there is greater threat to property from fires, but that there is higher incidence of human-caused wildfire starts. It is a fact that most wildfires today are human caused, though lightning remains a very common cause, and studies indicate that changes in climate are increasing the number and frequency of lightning strikes; Ferguson cites one study which suggests as high as a 12 percent increase per 1.8 degrees F increase in temperature.

Climate change — frequently a loosely defined term, (tragically, already used several times in this review) — is a hot, highly politicized topic, and one Ferguson makes a noted effort to elaborate on in specific terms throughout his writing. Understanding not just the rise in temperatures, but factors like the increase in the number of rain-free days, the measurement of snowfall and the timing of snowmelt, all help tell the story of why forests are increasingly stressed. The term climate change is not particularly useful in describing these complex factors. For instance, to understand pine bark beetle infestation, it is important to look at the change in winter low temperatures, because temperatures below 20 degrees F are required to kill larvae and help maintain populations. Ferguson references his writing with studies of temperature, rainfall, snowpack and more to illustrate the specifics of what climate change is and how it is altering conditions on Western lands and the patterns of wildfire.

To understand the complex interactions of conditions, policies, and practices that have gotten us to the present point, and the choices we face in managing forest lands in the future, we need sources of information that present us with clear, unbiased, unpoliticized exposition. “Land On Fire” is such a book. It seeks to be informative, but not prescriptive. It tells a complex tale, rich in historical insight and natural science of a relationship between land and fire that seems presently out of balance. And it cautions us not to be complacent about the reality of wildfire in the West. Larger, more destructive fires are, without question, in the future, and these will be increasingly problematic and expensive as they destroy property, and change the landscape and watersheds that supply us with water, fuel, building materials, recreation and so much more.

If you’re looking for a compelling read that will give you new perspectives on the Western lands you live in, drive, hike, bike and travel through this summer, check out Gary Ferguson’s “Land on Fire.”

Reviewer’s Note: “Land on Fire” was published by Timber Press, a publishing company in Portland, Oregon, committed to publishing a wealth of books on all things that grow. I would like to thank and acknowledge them as they made it so easy for me to get an advanced copy of “Land on Fire” for this review. I encourage you all to check out the many titles in their catalog on their website or in your local bookstore.

Mr. Ferguson will be giving a presentation, reading and signing July 1, 2017 at 3:00pm at Fact & Fiction bookstore in Missoula, MT.

Thanks for this great review! I am compiling authoring a “summer reading list” related to community wildfire resiliency and behavior change that I plan to publish as a blog on the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network blog (https://fireadaptednetwork.org/blog/). May I could quote (and link to) your review?