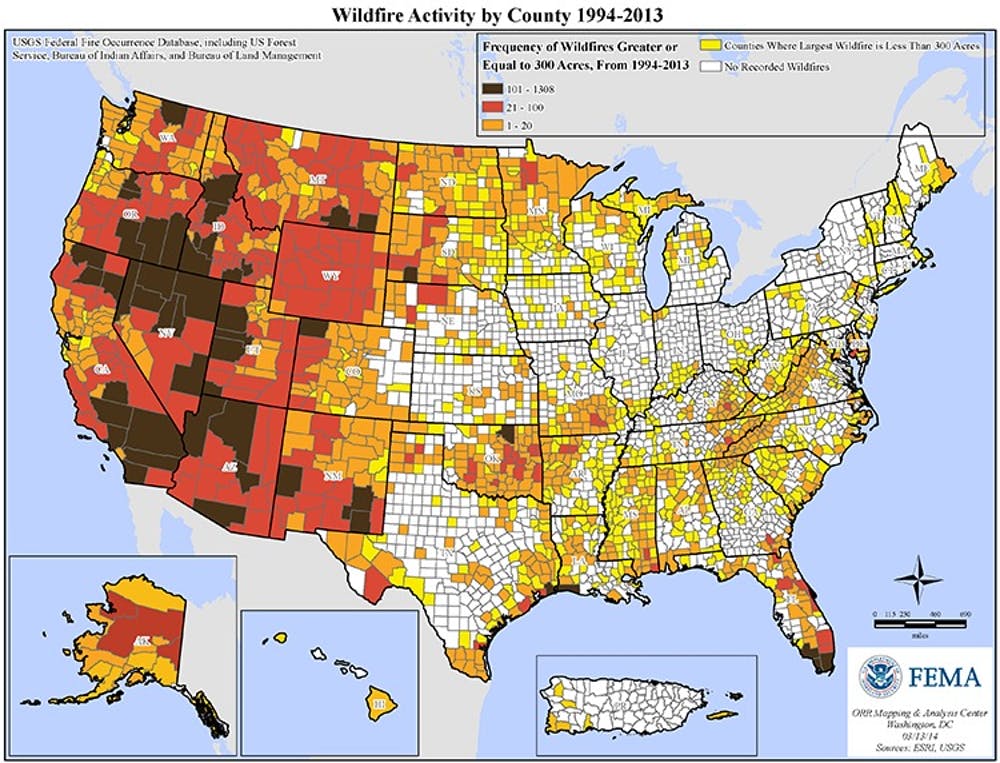

It is the dry season in Western states, which means that large swaths of land are burning or smoldering and are likely to remain that way until the snows arrive. The 2017 wildfire year started earlier and has scorched more acreage than normal. It is also far from over.

As wildfire trends worsen, it is increasingly important for communities in fire-prone regions to learn from past blazes and adapt to a more flammable future. Communities located in what researchers call “the wildland-urban interface” are due for tough conversations about the future.

Indeed, some communities are already grappling with the challenging policy questions that accompany catastrophic wildfires. To name a few: How much more development should local governments allow in landscapes that have evolved to burn? How should federal agencies manage the overgrown forests generated by wildfire suppression in the past? And as climate change further amplifies wildfire hazards, how can residents of the wildland-urban interface adjust?

Local media can be important players in those conversations. News reporting influences policymakers’ agendas and shapes public memories of disasters. However, past research has argued that the press is more interested in fanning the flames than digging down to root causes and finding a smarter way forward.

But in a newly published study of wildfire coverage in Colorado, my co-authors and I found a more complicated story. When communities face multiple wildfires in a row, local media do in fact raise the tough policy questions that need to be asked in communities at the wildland-urban interface – at least for a little while.

Looking for coverage patterns

My colleagues and I set out to study the patterns that appear in local media coverage of wildfires so that we could better understand what policy problems local journalists bring up, how they assign blame or responsibility, and whether these trends change over time.

Past research has suggested that the media are more likely to stymie disaster learning and adaptation than to encourage it. That’s mostly because reporters often ignore catastrophic wildfires’ systemic causes, while they focus on questions better tailored to urban blazes, such as who or what is to blame for sparking the fire.

That critique is largely fair, but it’s also too simple. As it turns out, we know little about how local media engage with the increasingly common occurrence of repeated catastrophic wildfires, which might inspire a different style of reporting. As a former journalist myself, I was especially curious to know more.

These questions sent us digging into a stack of 1,702 news articles published by local media in Colorado before, during and after the 2012 wildfire season – the state’s worst in history. As we analyzed these stories, an unexpected trend appeared: Articles published on wildfires’ anniversaries were more likely to bring up tough policy questions than stories published at other times of year.

This didn’t match what we thought we knew about wildfire coverage or “anniversary journalism.” Going into the study, we had believed that commemorative stories often failed to connect the past with the present in a meaningful or critical way, and therefore were not very useful for learning.

Analyzing anniversaries

To explore this unexpected trend, we gathered a new sample of stories: commemorative coverage from the first, second and third anniversaries of Colorado’s catastrophic 2012 wildfires, which burned simultaneously in Colorado Springs and Fort Collins. Colorado Springs experienced a second catastrophic fire in 2013, so we collected anniversary coverage for it as well.

As we looked for patterns among the anniversary stories, and between those stories and articles from an 18-month period around the blazes, we paid close attention to whether stories raised policy problems and identified actions that government or individuals should take. We also looked closely at whether policy stories focused on systemic causes of wildfire disasters, such as human development in fire-prone areas, or merely on symptoms of these problems, such as needing more slurry bombers for fighting fires.

Lastly, we looked for examples of local media connecting the past to the present and future in meaningful ways. Communication scholars call this “collective prospective memory-making” – the practice of identifying what needs to be done now and in the future based on a memory of a past event.

Introspection at year one, then business as usual

We found a clear learning and adaptation “signal” during wildfires’ anniversaries, which stood out against the “noise” of wildfire reporting over the rest of our sample. Anniversary coverage was much more likely to bring up policy problems connected to the systemic causes of human vulnerability to wildfire hazards – development in the wildland-urban interface, legacies of wildfire suppression and climate change, to name a few examples.

Many anniversary stories also made statements about what sorts of hazard mitigation actions still needed to be taken based on memories of past blazes. This “signal” was especially strong in wildfire anniversary coverage from Colorado Springs, the community that faced repeated catastrophic wildfires in consecutive years.

But there was also a surprising twist. Wildfires’ first anniversaries were the most promising periods for tough policy conversations. On later anniversaries, local media backtracked on this dialogue. As time passed, reporters took to comparing Colorado’s three major burn zones against each other with a focus on which was rebuilding faster and bigger, framing these later commemorations as a race back to the status quo instead of asking what communities should be doing differently.

Discussions that lead to change

Our findings show that local media coverage of wildfires appears to be more nuanced than originally thought. More specifically, the first anniversaries of catastrophic wildfires – especially repeated blazes – seem to be a salient time frame for getting to the roots of worsening wildfire hazards. If communities are going to have tough conversations about the future, these may be critical windows for doing so.

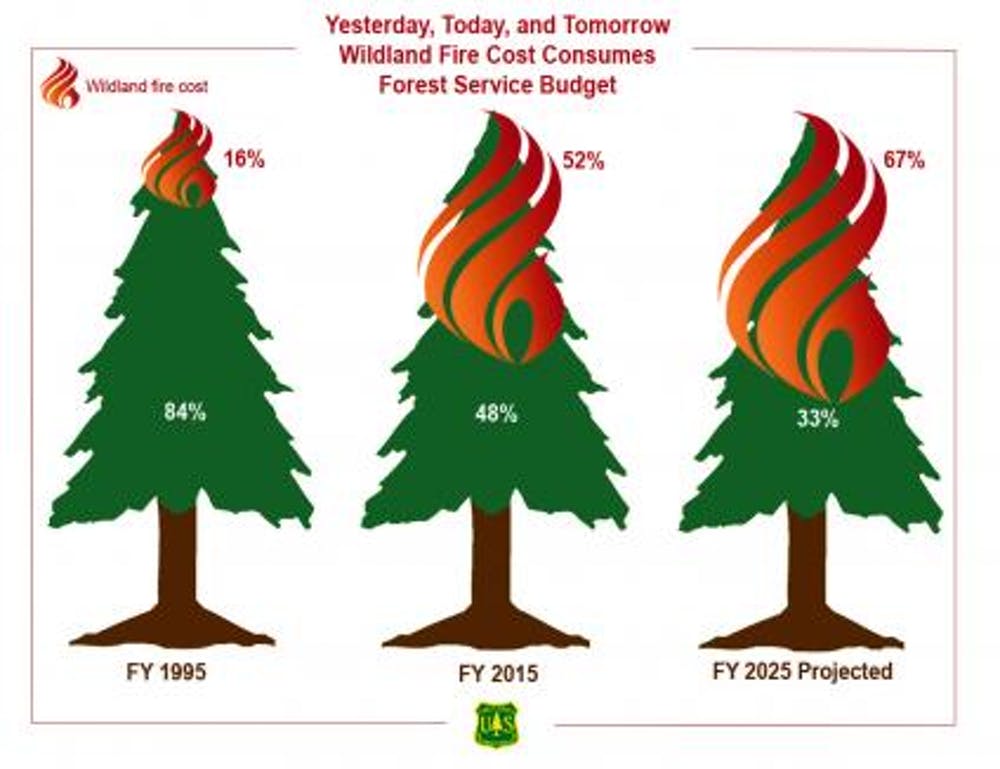

Going forward, it will also be important for communication scholars to study how local media signals affect policymakers and individuals. Ultimately, changing the conversation about wildfire matters only if the dialogue manifests in real changes on the ground. This year’s grim wildfire season, the U.S. Forest Service’s growing firefighting expenditures and our increasingly flammable future demand that we ask tough policy questions and then work to answer them with meaningful change.

Adrienne Kroepsch is an assistant professor in the Division of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Colorado School of Mines. This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Leave a Reply