Editor’s Note: In a three-part series continuing today, Treesource is exploring the potential roles of forests and wood products in addressing the global climate crisis.

Part 1 (Read it here): How can we use more wood, a renewable, biodegradable carbon sink, while also storing more carbon in forests across the U.S. and the world?

Part 2 (Today): What incentives and regulations are needed for landowners, forest stewards, corporations, governments and NGOs to change their practices and thereby make carbon storage a top priority?

Part 3: A look ahead to 2050. What could a more sustainable society look like, if forests and wood products were utilized in new ways?

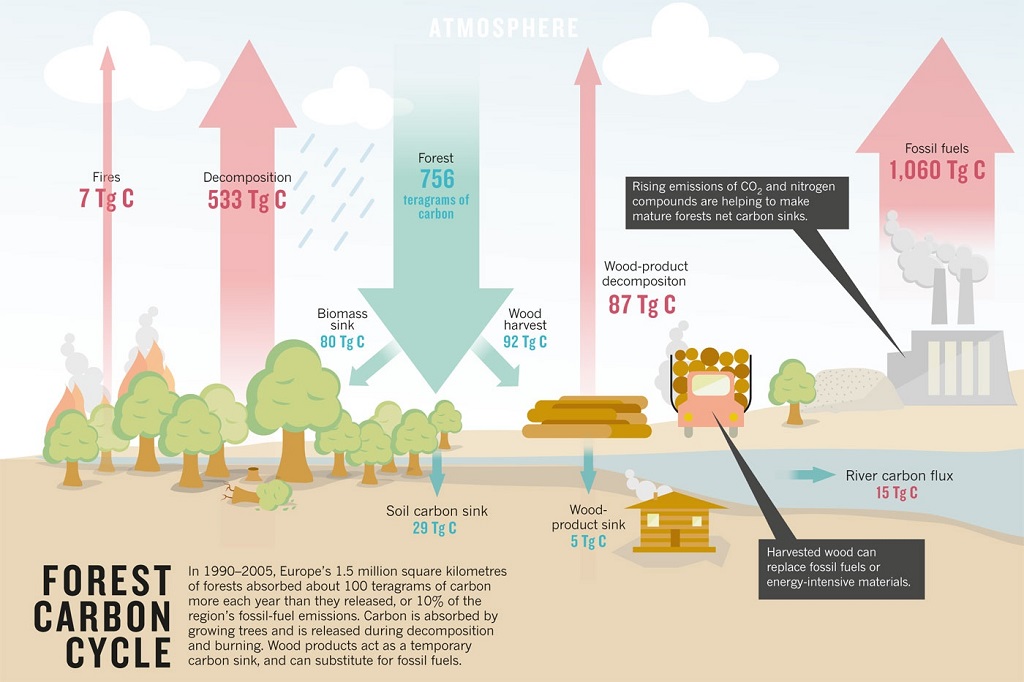

Forests provide one of nature’s most powerful systems for capturing and storing carbon: photosynthesis.

Trees inhale carbon dioxide and mix it with the water and sunlight they capture. Then they convert the carbon dioxide into oxygen and release it back into the air, and produce energy. The energy takes the form of a sugar called glucose. The glucose nourishes trees and is the building block that enables them to grow taller and broader. The carbon from the carbon dioxide is stored throughout the trees.

As long as trees hold onto their carbon, they reduce the concentration of greenhouse gases that are overheating Earth’s atmosphere. But when trees burn or die and decompose, their stored carbon is released once more.

That’s why forests worldwide are crucial in the fight against global warming. The Nature Conservancy’s study published in 2017 estimated that 37 percent of the greenhouse-gas problem could be solved by natural systems, with forests playing the biggest part. This solution is called natural carbon storage.

Here’s the challenge: As societies worldwide move away from use of fossil fuels (the combustion of which is the largest source of greenhouse gases), wood will be in far greater demand as a raw material. And that will require growing – and cutting – more trees for use in bridges, skyscrapers, homes, businesses, packaging, medicines and clothing.

The International Panel on Climate Change put it this way:

“In the long term, a sustainable forest management strategy aimed at maintaining or increasing forest carbon stocks, while producing an annual sustained yield of timber, fiber or energy from the forest, will generate the largest sustained mitigation benefit.”

But how can forests simultaneously provide more wood and more carbon storage?

Jad Daley, president of American Forests, has been working on this question for more than a decade in his capacity as a co-founder of the Forest Climate Working Group – a coalition 70-plus groups representing conservationists, forest owners, federal and state governments, and wood-products trade associations.

Daley urges adoption of a long list of policies that could elevate the role of forests in absorbing carbon dioxide, while also providing wood products and recreation areas – as well as protecting biological diversity and critical watersheds.

Several such policies were included in the Federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act that passed Congress in late 2021. “This is one of the most significant forest investments in our nation’s history,” Daley said. “The new law will deliver more than $5 billion for wildfire resilience, helping to address a crisis fueled by climate change.”

In addition, the act incorporates language from the REPLANT Act to provide the U.S. Forest Service with permanent, dedicated funding to reforest areas burned (or otherwise damaged by natural forces) so severely they cannot regenerate on their own.

The Forest Service has a reforestation backlog of 4 million acres, most of which burned in wildfires driven by climate change.

Separately, the “Healthy Streets Program” being established in the Department of Justice will be “a big step toward tree equity and climate justice in our cities,” Daley said, citing plans to plant more urban trees and to deploy “cool surfaces that together can reduce urban heat islands and improve air quality in underserved neighborhoods.”

Now, the Forest Climate Working Group is focused on the Build Back Better legislation that was passed by the U.S. House and has since stalled in the Senate. Daley said that legislation could significantly expand programs that promote the use of forests in mitigating climate change.

Meanwhile, the American Forest Foundation (AFF), another of the climate group’s founders, is working with family forest owners to promote “carbon management” on their lands. America’s 11 million family-forest owners manage 38 percent of the nation’s forests, so their participation is vital if trees are to help sequester more carbon. Governments alone cannot provide the level of investment needed to combat climate change. Hence, the push for new regulations and incentives to encourage private investments.

AFF’s Family Forest Carbon Program is one such effort. It focuses on forest-management actions that could increase the amount of carbon stored by private timber stands, regardless of their current carbon stocks.

Under this program, corporations looking to reduce their carbon footprint, in part by purchasing carbon credits, would sign contracts (lasting 10 to 20 years) with individual family forest owners. These owners would then guarantee a specified amount of carbon storage on their property during the contract period. By employing certain prescribed forest-management techniques, the landowners would expect to increase their forests’ carbon sequestration as the decades passed. In addition, the landowner would grow more wood, so would benefit from that added value as well. Society would benefit by having more wood available to displace fossil carbon products.

By contrast, the California Air Resources Board has developed a carbon credit program under that state’s cap-and-trade program. CARB targets forests with existing above-average carbon stocks and negotiates agreements that maintain and increase those stores of carbon. The state typically requires a contract of 100 years or more.

The wide diversity of carbon-offset programs — and their varying methods for measurement and verification, and the lack of standards — add uncertainty and make it more difficult and expensive to access funding from the many corporations that want to buy carbon credits, industry officials told Treesource. Investors want a forest-credit program to be transparent, with credible verification and monitoring of its carbon sequestration, and a trustworthy reputation in domestic and international marketplaces.

The Task Force for Scaling Carbon Markets was created to establish this needed consistency and trust following the Paris Climate Accords of 2015. The result was the adoption of rules for Article 6 at COP 26 in Glasgow in 2021, including operating principles, a governance structure, and legal and contractual frameworks.

The Task Force for Scaling Carbon Markets was created to establish this needed consistency and trust following the Paris Climate Accords of 2015. The result was the adoption of rules for Article 6 at COP 26 in Glasgow in 2021, including operating principles, a governance structure, and legal and contractual frameworks.

The task force intends to develop both high-integrity carbon markets and robust, transparent and liquid markets. If these dual goals are accomplished, then massive amounts of financing could be mobilized to help reduce greenhouse-gas concentrations, said Paula VanLaningham, head of carbon pricing for S&P Global Platts.

At COP 26 last year, the Natural Carbon Solutions Alliance, which is part of the task force, unveiled a new Natural Carbon Solution Investment Accelerator, which aims to create corporate demand for a gigaton per year of forest-based carbon offsets by 2025.

That would represent $10 billion to $100 billion of investment annually, depending on the price per ton of offset. Presumably, such demand would send a powerful signal to forest landowners and managers to adopt practices that capture more carbon.

And there is potential for more gigatons and possibly trillions of dollars in investment, according to the Task Force for Scaling Carbon Markets. The adoption of Article 6 could provide a path for the development of fledgling markets for other services that forests provide, such as water quantity and quality, and biodiversity, sources told Treesource.

Rita Hite, CEO of the American Forest Foundation, stressed the importance of “rules for the road” so companies can easily participate in the carbon offset market.

Right now, “it takes 15 to 20 conversations with each corporation to get them comfortable with the Family Forest Carbon Program,” Hite said. That timeframe doesn’t allow for the rapid scale-up required if forest carbon offsets are to provide a meaningful contribution to greenhouse gas mitigation, she said.

The new rules in Article 6 should pave the way, but Hite believes more help is needed.

Hite said the U.S. Department of Agriculture could substantially improve the carbon offset market. Several proposals pending in Congress would allow USDA to provide that support.

The Rural Forest Markets Act would “de-risk” investments in forest-based carbon credits and make them more attractive to corporate buyers. (Such risks include forest fires, insect infestations and drought.) It’s a role the USDA already plays with agricultural crops, Hite said.

In addition, the Growing Climate Solutions Act would expand the USDA’s ability to provide technical assistance in support of expanding carbon markets. With 11 million family forests, Hite said, landowners will probably need a lot help determining whether carbon offsets align with their own goals.

Another role for USDA is expanded research on innovative ways to use wood, such as mass timber and bio-based products.

AFF supports the use of wood products as part of the climate solution, along with more carbon in the forests, Hite said. “We need to use more wood products,” she said, to accomplish that AFF supports expansion of the U.S. Forest Service’s wood innovation program to jump-start those products.

In addition, several stand-alone bills introduced in both the House and Senate would put a price on fossil carbon paid by fossil fuel companies, and would authorize a rebate of the revenue to help Americans adapt and invest in their homes, transportation and other purchases intended to reduce their carbon footprint.

These bills also would include a carbon border adjustment to protect domestic producers and force foreign producers to pay for their fossil carbon use. The European Union plans to put a carbon border adjustment in place in 2023, and Canada is considering the same. Economists across the political spectrum support a carbon price as an essential tool to achieve carbon-reduction goals of 2030 and 2050.

An established carbon price would create an economic incentive for businesses to change their practices and behaviors, i.e. their fossil carbon emissions. And a border adjustment would create the incentive for other countries to adopt a price as well – rather than paying the carbon fee at the border.

Moreover, establishing a carbon price could create a powerful advantage for wood products, since they typically have low carbon footprints — and since longer-lived wood products store carbon for their full lifespan. The carbon price could establish worldwide certainty for the market value of carbon, thus enhancing the natural carbon offset markets.

What’s the bottom line? Forests and wood products are an important part of the natural carbon storage system, and thus they are crucial to achieving worldwide climate goals.

Recent legislative successes in the U.S. and the adoption of Article 6 in Glasgow have put the edge pieces around huge puzzle. But many pieces of the puzzle remain in the box, awaiting their placements.

Leave a Reply