My wildland fire experience began in 1973 at a U.S. Forest Service fire research lab, conducting early fire behavior studies. My time on firelines across Alaska and throughout the lower 48 states spans from 1978 to 2012.

My wildland fire experience began in 1973 at a U.S. Forest Service fire research lab, conducting early fire behavior studies. My time on firelines across Alaska and throughout the lower 48 states spans from 1978 to 2012.

I have been teaching about fire in one form or another since 2012 and continue today. That 44-year period is nothing compared to geologic time, but it has had an impression on me.

Overall, I have observed temperatures getting hotter earlier in the year, rising higher during the summer and remaining hotter later in the year. Humidity (air moisture content) has followed the same pattern: lower earlier in the year, staying low throughout the summer and later in the year. Nightly humidity recovery also does not seem to occur as it once did.

Under these conditions, moisture in live and dead forest vegetation (which is fuel) dries sooner and remains dry longer. Drought is becoming more common and frequent. This stresses trees, particularly in fire-prone areas like southerly slopes where sunlight shines earlier and longer. Insects and disease then take a fatal toll on stressed, overpopulated stands of trees.

Forest fuels have simultaneously been increasing in biomass as we’ve become adept over the past century at extinguishing fires. This is true in all forested stands to one degree or other, but especially true when lightning- and human-caused fires historically burned every five to 10 years in our fire-adapted, fire-prone ponderosa pine stands.

Getting drier

Dead forest vegetation has been accumulating, drying and remaining cured longer. This accumulation of dead and live woody biomass has been getting drier (especially in fire-prone or fire-adapted areas, southerly aspects, low-precipitation areas, etc.). Our homes are also fuel.

The size of forest fuels also greatly influences fire behavior. A quarter-inch diameter twig dries sooner, ignites faster and burns quicker than a 30-inch diameter log because small-diameter wood has more surface area than larger material. In fact, it is often hard to get a log that size to burn at all unless it dries out. The drier the wood with more oxygen applied (wind), the hotter it will burn.

Overall, it was easier to put out a fire in the 1970s. Fires typically (with a few regional exceptions) burned fewer acres, nighttime humidity recovered well, firefighters easily found water sources and air tankers could really make a difference with a single retardant drop.

There was also less risk as hazardous firefighting conditions were fewer and farther between. Firefighters often used direct attack on a fire’s perimeter. Now, hazards often force them to use indirect attack by constructing firelines and conducting back burns a safe distance from the perimeter — or withdrawing altogether until conditions become safe to engage.

Things heated up

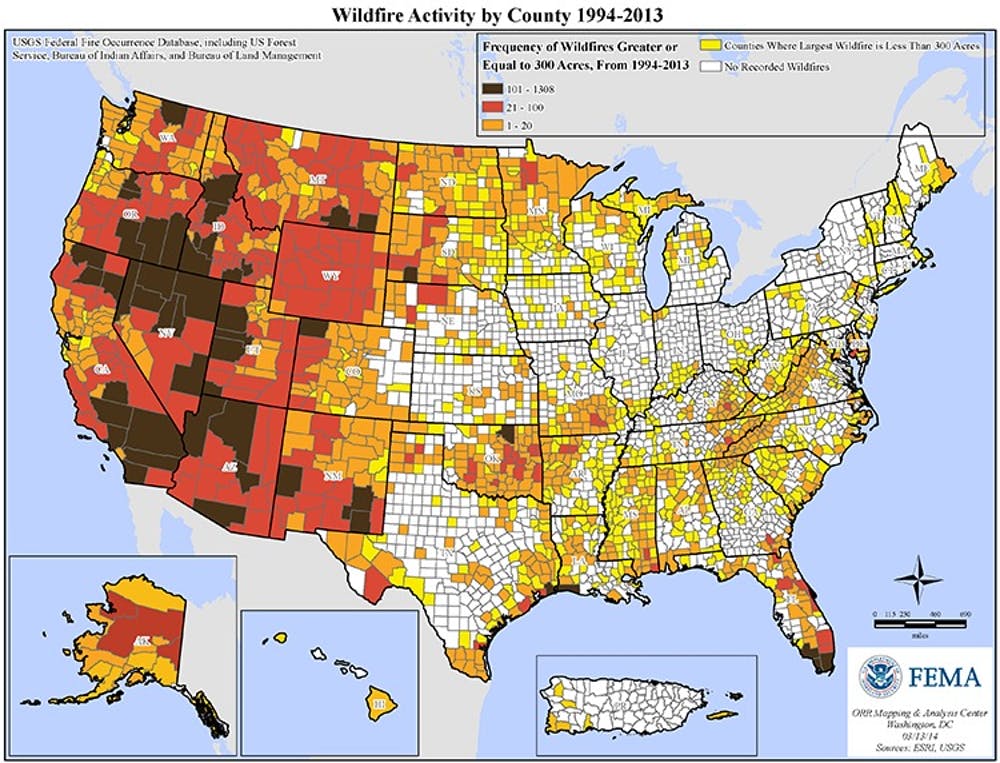

In the mid- to late-1990s, fires began burning hotter; air tankers needed to make more retardant drops and water was less effective. Fires in the last five years have become normally (on average) as huge in size, intensity, and severity as the exceptions were in past decades.

Hazards have dramatically increased and exposed our firefighters to more risks. Firefighter safety is always the primary objective and no fire is worth risking a life. For that reason, there is less direct attack on fires than before.

It has always been easier and safer to suppress fires in responsibly managed forests, where ecosystem health, fuels reduction, wildlife habitat and overall diversity are the primary objectives. This is true today.

Firefighters use the term red flag conditions to describe when lower humidity, and higher temperatures and winds reduce fuel moisture content. Anything organic can then burn hot if an ignition source starts a fire. Will removing the biomass of live and dead woody fuel affect fire intensity and severity? Of course, it can. The less fuel to burn, the lower fire intensity.

Good at both

Fuels management is one of the few things we can do along with suppressing fires. We are good at both. Terrain is normally out of our control, as is weather. But we can manage forest fuels.

Managing fuels through responsible forest management reduces wildland fire risks, hazards, intensity and severity. It also improves overall forest health and wildlife habitat.

We have opportunities and choices to make. We can manage our forests responsibly by easing fire back into fire-adapted ecosystems through careful harvests, controlled burns, and various tools in our management toolboxes. Fire and resource management agencies across the West are examining various suppression strategies as an over-abundance of forest vegetation, climate change and more homes (which are fuels, too) in fire-prone areas make massive fires increasingly common and dangerous to residents and firefighters.

Science a key

We can use science to manage fires to increase firefighter and public safety, foster forest health, promote fire resiliency and nurture wildlife habitat — while improving economic opportunities that will bring jobs. Or we can let it burn hot and let it go up in smoke.

We can never stop all wildland fires through responsible forest management or otherwise.

But responsible forest management reduces wildland fire risks and hazards. It also reduces fire intensity and severity when they burn in fire-adapted, fire-prone environments.

Daniel Leavell works at Oregon State University, College of Forestry Extension, as Assistant Professor of Practice in Forestry, Natural Resources, and Fire Science assigned to Klamath, Lake and Harney counties. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Oregon State University and his Ph.D. from the University of Montana.

I should think that some of the fuel mgt. could deliver much of that fuel to a biomass power plant- at least in areas reasonably accessbile- if a biomass plant in the region. Unfortunately, there is ferocious resistance to biomass power plants, especially in New England. Too bad, because having a biomass market is great for silvicultural work and fire protection.

Joe Zorzin

“a forester in Mass. for 44 years”

Dr. Leavell. Your paper comes at an opportune time as politicians and the media are all demonstrating their collective lack of knowledge on this complex subject. Your paper demonstrates the value of the long term experience you have in various ecosystems. I appreciate your continuing effort to inform people, including fellow foresters.

I was not aware that managing fuels through responsible forest management is the best way to reduces wildland fire risks, intensity, and severity. My brother was writing an essay about how to prevent wildland fires, and we are looking for advice. I will let him read your article to help him understand more about the benefits of responsible forest management.