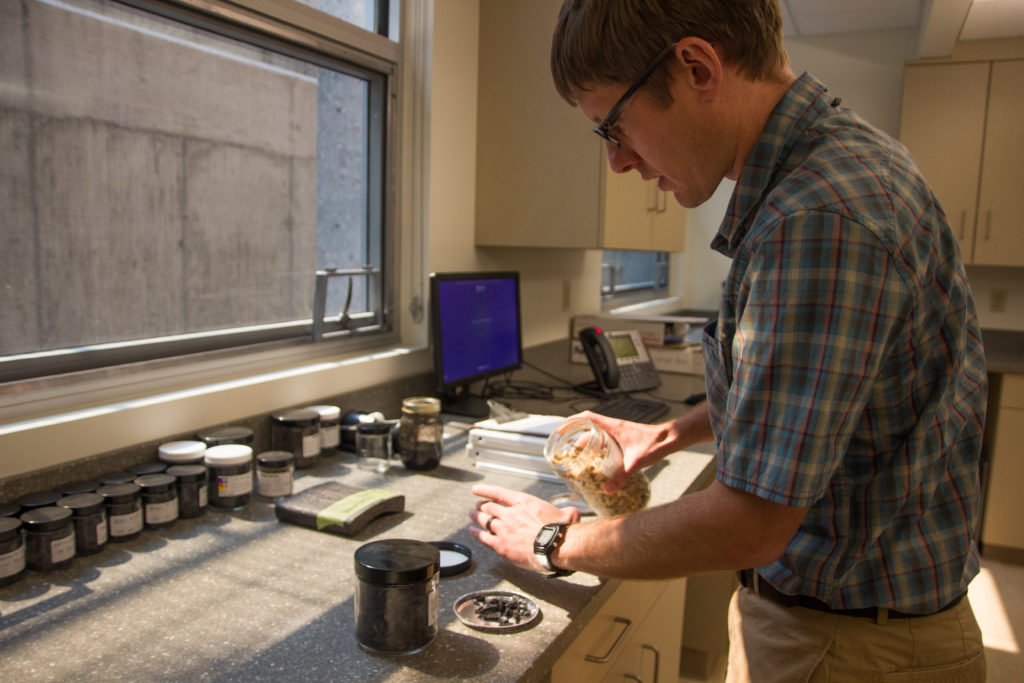

Nate Anderson surveys the samples of biochar on his lab table.

Some look like charred wood chips. Others have been transformed into pellets. Still others are shiny, like crystals. These samples have been “activated” and are similar to what you’d find in a water filter. One jar holds bio-oil, which smells like the condiment Liquid Smoke.

Seven years ago, Anderson knew little, or nothing, about biochar. Today, it is just one of many forest products he studies as a research forester at the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula, Montana.

“Biochar is one of many products that we make from forest resources,” Anderson said. “The idea of carbonizing our forests does not capture the spirit of the research that’s going on right now.”

Despite some public misconceptions, biochar is swiftly becoming a more viable option for land managers with a wide range of management goals. Some biochar scientists are hopeful that within five years, there will be an active and demanding market for this forest product.

Essentially, biochar is charcoal that is used as a soil amendment. Any kind of biomass (woody byproducts, crop residues, even manure) undergoes pyrolysis, which results in the carbonization of the organic matter. When this matter is spread on soil, it is considered biochar.

Anderson said the motivations behind creating biochar are four-fold: waste management, climate change mitigation, soil quality and renewable energy production, of which biochar can be a byproduct.

Biochar is hailed for its carbon sequestration properties, as it can hold carbon in the soil for hundreds, even thousands of years. But Anderson said it also has significant potential as a commercial product.

Take the example of a federally managed forest in the West. After harvesting a parcel for timber, excess biomass is often trimmed from the trees and piled. Then, to prevent the accumulation of dry, highly flammable fuels, the slash piles are often burned.

Anderson said converting this waste to biochar is one way to monetize something that many people consider refuse.

Biochar can be sold to crop farmers as a fertilizer additive, livestock farmers as a feed additive or even other forest managers to be put back into a forest landscape.

A recent study found that biochar on a wheat field increased yield by more 20-30 percent, and another study found that biochar along roadways can mitigate the negative impacts of road salt.

Anderson said the creation of biochar does emit greenhouse gases, but the controlled process results in fewer emissions than burning the same pile of slash, for example. Not only that, but the piles could be used in the production of energy.

“One of the things we like to think about is these materials that are waste products that are being burned,” Anderson said. “Using those in a controlled combustion to produce heat, we might offset some fossil fuels and we might improve the emissions profiles of those materials that are going to get burned anyway.”

**

Until recently, one of biochar’s biggest challenges has been spreading it at operational scale on demanding landscapes, such as a 100,000-acre forest in the Rocky Mountains.

Enter the prototype biochar spreader.

Completed in 2016, the prototype spreader means inaccessible mountain landscapes can more easily and quickly receive an application of biochar.

Keith Windell, a mechanical engineer at the Missoula Technology and Development Center, designed the spreader. He said the design was inspired by highway salt spreaders, but it’s been modified to attach to a logging forwarder.

The spreader can send material across 40 feet and is weather-resistant.

Though it’s only been used on small test plots, the prototype spreader is about to be used on its first real project.

Debbie Page-Dumroese, a Forest Service research soil scientist, said the spreader is about to be shipped from Missoula to Stanislaus National Forest near Arnold, California, for the largest biochar spread. They’ll treat about 10 acres of harvested ground and another 5 acres in an unlogged area.

“In the past, it’s been by scooping out five-gallon bucketfuls,” Dumroese said. “You can’t do that on a large scale. This is a big technological leap forward for us.”

She said biochar has a number of positive impacts on an ecosystem that go beyond sequestering carbon.

“If you could increase organic matter by 1 percent, you can increase water-holding capacity by 27,000 gallons [per acre in six-inch surface soil],” Dumroese said.

Dumroese said her next study will focus on the connection between biochar and resilience – if biochar can increase tree health and resistance to insects and disease.

**

The possibilities, it seems, are endless.

Dumroese said there are a couple of reasons more biochar isn’t used. It hasn’t been readily available until recently, and Dumroese is looking into low-tech and cheaper methods of creating biochar that could be more accessible to small and private landowners.

Biochar also responds differently to different soils. It responds best in coarser soils, but it could take years before land managers see results on finer-textured soils.

Dumroese said the science has progressed past much of the myth: Scientists know how to prevent improper pH balances or chemical additives.

“We’ve never had any negative impacts of putting biochar out on soils, and we’ve worked on range and mined and forest sites,” she said. “That in and itself is one testament to biochar.”

How can i get more information on the tests being done? Do you know of any other applicators for crops to get into the ground and not just broadcast. We produce; at a ton per hour; very high carbon and surface area bio-char. May we bid on supplying char for your tests?

I’d like to know more about the form the biochar is in when it’s used in the prototype spreader. I’ve heard that it can be pelletized, which makes handling and spreading easier, and cuts down on the dust.

for production you want the smallest most consistent size. we use sawmill sawdust, some use larger up to chips; some applications want even smaller.

char is very abrasive; which would be hard on pellet equipment. would also need a lot of binder.

Great work guys! There are also some alternatives that can produce biochar in the forest using the same hand crews that now do pile and burn. See our work with the Umpqua Biochar Education Team at http://www.ubetbiochar.blogspot.com

I wish more energy would be put into educating and getting bio-char in the ground. Most of these back-yard burners emit pollutants and most of the char is not high quality; yes it is still good for the soil, but so is ash. We need more education of the farmers to the benefits. If the market is there we will build the clean commercial plants that produce high quality char.

Jim, actually the char from some of our simple kilns is very high in recalcitrant carbon – it is good quality char. We do our best to burn the smoke in the process so it is not very polluting. It is much cleaner than standard pile burning. These simple techniques are suitable for what you might call “stranded biomass,” that is too remote or too thinly distributed on the landscape for it to be economical to transport to an industrial facility. I think we need a spectrum of methods for making biochar. No one size fits all.

Yes there can be many ways to make char, but it doesn’t matter who, what, where it is being made if there is no market. My concern is in a new industry that there will be poor quality char distributed and hurt the market. There are many studies out there that do not show any improvement; one must assume it was not good char and raises questions to potential customers. I do appreciate all the work you do for Bio-char. As I mentioned above if the market is developed the plants and mobile units will be built.

Spot on Kelpie!!

Societies need to move from complaining and talk to real meaningful action. This happens around the world, only when we do something will we change something.

The Biochar Journal,the IBI Team are about cascading uses and based on restorative practices.

Best regards from under’Down Under’ in Tasmania.

http://www.terrapretadevelopments.com.au

Feed char to livestock.Goes in as char comes out as biochar loaded with micro organisms. Increases feed efficiency, daily gain and lowers methane emissions. It gives the rumen organisms a place to work, adsorbs toxins and I believe somehow inactivates herbicides. Using char mixed with sea salt I think there is deactivation of the fungal produced alkaloids in tall fescue.

Furnish the $ and I will find out.

Enough tests have been done; what needs to happen is to get FDA approval. Currently you can not feed bio-char to livestock in the U.S.

Up to 90% of all char in Europe is used in livestock; either as bedding or feed. Results are good to great and the industry is growing. Many people consume charcoal; but the USDA does not allow it as feed to animals that are consumed. Not sure how long it will take; it only took us 30 years to figure out fuel injection was a good idea.