Editor’s Note: In a three-part series starting today, Treesource will explore the potential roles of forests and wood products in addressing the global climate crisis.

Part 1: How can we use more wood, a renewable, biodegradable carbon sink, while also storing more carbon in forests across the U.S. and the world?

Part 2: A detailed look at the policy choices that governments, businesses and individuals must make.

Part 3: A look ahead to 2050. What could a more sustainable society look like, if forests and wood products were utilized in new ways?

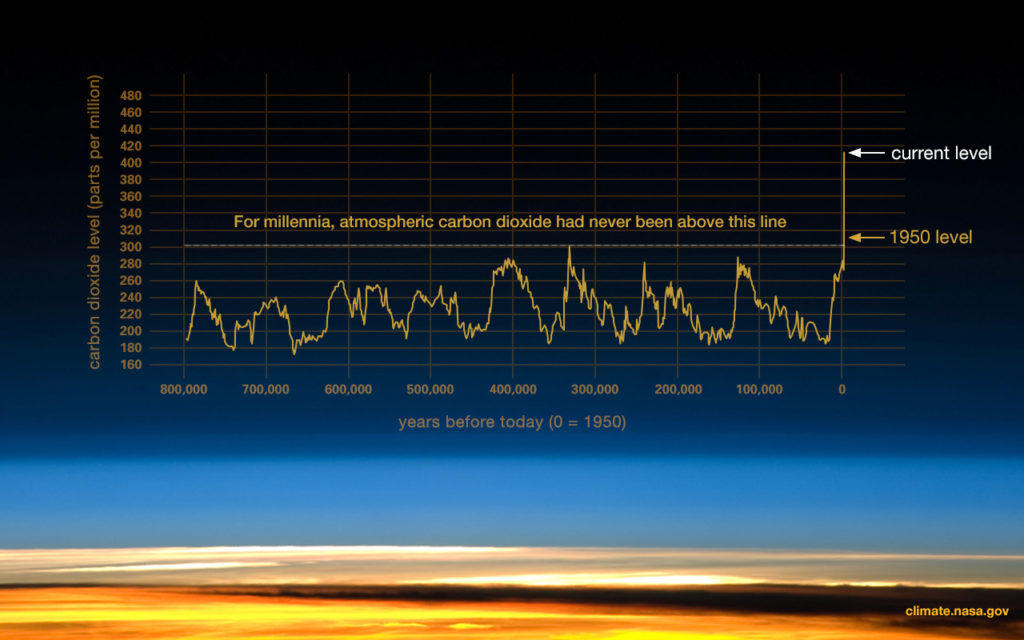

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a warning that one United Nations official called “a deafening, piercing smoke alarm going off in the kitchen.” For the world to avoid ecological and social catastrophe, the scientists said, humans must quickly and radically transform the systems that provide energy –- by ceasing to burn fossil fuels. Greenhouse gas emissions, they said, must drop by half no later than 2030, and to zero by 2050.

Three years later, in August 2021, the IPCC returned with what the UN’s secretary general labeled “a code red for humanity.” The wildfires, droughts, hurricanes and brutal cold snaps of recent years were evidence that so much carbon dioxide is already cooking the atmosphere that further calamities are inevitable.

And yet, the significant curtailment so urgently needed has not happened. Instead, greenhouse gas emissions actually increased between 2018 and 2021, the IPCC said.

Action is needed.

Now.

On many fronts.

In addition to phasing out fossil carbon, one of the remedies consistently mentioned by the IPCC – and gaining heightened attention in recent years – is “natural carbon storage.” The capture and storage of carbon through natural processes in the soil, wetlands, forests and wood products –- followed by its monetization –- began more than 20 years ago. Now, with corporate and organizational pledges of “net-zero” emissions growing by the week, groups are scrambling for ways to accomplish those goals. Natural carbon storage is part of the answer, said Jad Daley, CEO of American Forests, the oldest forest conservation organization in the U.S.

Daley explained: “Imagine we have this ‘magical device’ that can suck carbon dioxide out of the air and give us back oxygen, while storing the carbon in a form that provides wildlife habitat, a water filtration and storage system, a renewable, biodegradable building and packaging material. … Oh, we don’t have to imagine it, we already have trees in forests.” In fact, Daley believes the world is entering a heyday of intensive forest rejuvenation and increased wood-products use in response to global warming. Both, he said, are possible.

The science of forest growth provides evidence of the potential to produce more wood and to store more carbon by instituting longer growing periods between timber harvests, and by using different practices to grow and store more carbon in the forest. At the same time, researchers believe cities and nations could emit less carbon by using wood as a building material rather than concrete, steel, brick, aluminum or other energy/carbon-intensive products.

The challenge, of course, is how to grow more trees and use more wood simultaneously, said Barry Ulrich, director of The Nature Conservancy’s American Forest Carbon Initiative. “Nothing we are doing is designed to cut out the [wood products] industry; it is not about stopping harvesting. It is about doing it (capturing more carbon and more wood) sustainably. … The transition to doing both is the challenge.”

Antony Wood, CEO of the Tall Building and Urban Habitat Council, was a keynote speaker at the International Mass Timber Conference in spring 2021, during which he presented his vision of cities as carbon sinks. A metropolis stores carbon when wood is used for the built environment, he said, rather than the concrete and steel favored for more than a century. But greater utilization of wood products necessarily means increased timber cutting and milling.

In 2017, The Nature Conservancy led an international team of scientists to determine how much natural carbon storage is attainable and what actions would have the greatest positive impact.

In 2018, a second paper assessed the carbon storage potential of U.S. forests. The report’s conclusion: It would be ecologically possible to increase the use of forests for carbon storage while also boosting timber harvests for the construction of “carbon sink” cities.

“We can absolutely do both while making our forests more resilient to the changing climatic conditions,” said Daley at American Forests. “But we have to recognize that techniques for forests in Vermont and in Arizona will be very different, so the policy framework to accomplish these goals needs to be planned and implemented locally.”

Wood products were not addressed directly in The Nature Conservancy paper, but harvesting to meet the needs of people for construction materials, furniture, packaging, paper, energy was acknowledged as necessary. Said TNC’s Ulrich: “The potential benefits of using wood, like cross-laminated timber and other forms of mass timber, for creating wood-based mid- and high-rise structures in cities worldwide are substantial.”

Joe Fargione, lead TNC author of the U.S.-focused paper, modeled a variety of techniques to show the magnitude of potential benefits. Forests in the U.S. have captured and stored 12% to 15% of domestic fossil-carbon emissions for more than 50 years. How much more could be stored, Fargione asked, if the nation launched a full-scale effort? The answer: another 20%.

The combination of existing and potential natural carbon storage projects could capture one-third of the United States’ greenhouse gas emissions problem, according to the TNC report. The remaining two-thirds must come from reducing fossil-fuel emissions or via technological carbon capture and storage. Direct air capture is one example, but is phenomenally expensive at present.

Forests provide the greatest natural carbon storage potential, through planting new trees, growing existing stands longer between harvests and improved forest management practices. Said Fargione: “Certainly, there is opportunity to do targeted thinning to protect forests that are the most out of whack from a fire-regime standpoint or where watersheds or old-growth forests are threatened.” TNC advocates “thinning and burning in combination to accomplish restoration of the forest,” or so-called “carbon defense,” he said.

To address the entire country and its diverse forest ecosystems, a number of simplifying assumptions were necessary for the TNC-led analysis. For example, the team assumed that all “natural forest management” lands would see a harvesting hiatus for 25 years. At the end of that period, the resulting larger-diameter trees would have stored more carbon – but also would provide more wood. In addition, the rotation age of intensively managed forests (primarily in the Southeast and Pacific Northwest) would be extended.

Fargione acknowledged that the condition of the land in various regions would dictate the actual management actions. The “devil is in the details,” he said. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, but it is difficult to model all the different possible forest treatments in one nationwide study.

Christine Cadigan manages the Family Forest Carbon Program for the American Forest Foundation (AFF). The program is a joint project of AFF and TNC, targeting the smaller forest landowners who represent about 38% of all forest land nationwide and who offer a major opportunity for more carbon capture. However, these small forest lands also represent about half the log supply for domestic sawmills. Thus, the Family Forest Carbon Program, which is intended to wrestle with the devil in the local details – the sweet spot where a landowner can provide logs, store more carbon, create wildlife habitat and protect water quality. Meeting such divergent goals takes a lot of work and solid partners in research: at TNC, universities, the U.S. Forest Service, practitioners and landowners. “As we develop the practices, we always keep those conservation goals in mind,” Cadigan said. “We won’t adopt practices that have a carbon benefit but don’t also meet those other conservation goals.”

As scientists and program managers dive into the details, they are finding opportunities to accomplish a combination of goals – but again, the methods vary by forest ecosystem and region. In Eastern hardwood forests, for example, landowners must create openings in the forest.

In the 1990s, New Jersey Audubon and others found that neotropical birds were declining in number in the northern forests where they migrate to breed.

One of the major culprits: lack of foraging habitat.

One of the answers: more harvesting to improve avian habitat, while also providing logs for regional manufacturers.

Where do carbon offsets figure into the picture? For two decades, carbon offset programs have focused on large ownerships because of the expensive verification and measurement requirements borne by landowners. The contracts often required a 100-year term, more than the owners of small tracts are willing to consider. The Family Forest Carbon Program takes a different approach, focusing on carbon increase over time rather than on a forest’s existing carbon. Therefore, they pay landowners to implement practices that will increase the amount of carbon stored over a shorter period, say 10 to 20 years.

Ullrich stressed: “Carbon offset sales require an intensive vetting process, during which corporations can show they are first reducing their operational emissions.”

Forest management is also modified. Practices tested in central Appalachia include a prohibition on “high-grading,” a practice that allows bigger trees and more valuable species to be harvested and the rest to be left behind. Cadigan said high-grading can result in a shift away from oak, hickory, walnut and cherry trees, which provide valuable lumber and excellent food for wildlife. By working with landowners to modify harvests to retain some of those larger trees and provide seeds for a new forest, these species will continue to grow and store carbon –- and, in time, provide valuable logs.

The financial part of the bargain involves carbon offsets –- paying forest owners upfront for some of the carbon they will store and paying for more carbon later. The landowner can still sell some of the trees and thereby create desired habitat, while the modified harvest method produces more carbon and manufacturers get logs. This approach, along with Fargione’s example of “defensive carbon management” to reduce wildfire severity and insect risk, are just two of many practices where the multiple goals of carbon storage, healthy forests, wildlife habitat, wood production and watershed protection can be synergistic.

How carbon offset markets are structured and the potential for unintended consequences cause some forest owners and wood manufacturers to be cautious. One of those is Paul McKenzie, the vice president and general manager for F.H. Stoltze Land and Lumber, a 109-year-old company in northwest Montana. Stoltze has almost 40,000 acres in timber management, as well as a sawmill that is fed from its own land and a collection of small private, state and federal lands.

McKenzie worries that paying a landowner to leave the forest untouched for 10, 20, or 30-plus years has significant risks. He explained: “The national forests in Montana have become a carbon source rather than a sink because of mismanagement over the past 30 years. Bark beetle epidemics and severe wildfires have killed extensive areas. … Not only that, but the mills would go away unless there is another source of logs.”

What is needed, McKenzie said, is more markets for the smaller trees that need to be thinned from overcrowded Western forests – and which could be used to store carbon in wood products for longer periods. Stoltze has embarked on one such effort.

McKenzie stressed: “We can’t look at carbon and forests with tunnel vision. Forests provide habitat for wildlife, serve as water storage and filtration systems (some of Stoltze’s lands are under a conservation easement to protect the city of Whitefish’s water supply), provide a sustainable supply of renewable, biodegradable products and store carbon in the trees and the products.” The design of any carbon market should strive to avoid unintended consequences, he said.

McKenzie would like to tie the carbon revenue stream to actions that make the forest healthier – more resilient and more resistant to disturbances. And he said he likes the concept behind the pilot project in Pennsylvania by the American Forest Foundation, which is expanding to the Upper Midwest and Northeast, where payments are tied to better forest management practices that produce more carbon. That link can lead to better overall forest management to meet landowner objectives and carbon objectives, McKenzie said. “History has shown us when we focus too narrowly, we get in trouble,” he added.

Katie Fernholz, president of Dovetail Inc., a consulting forestry firm and think tank based in Minnesota, provides a more optimistic outlook. Can the U.S. grow and store more carbon while also harvesting more timber? “Yes!” she said,” if we do it carefully, using our scientific knowledge. We must tailor the methods and practices to the forest ecosystem, land ownership goals and robust policy that avoids the unintended consequences.”

Coming next: In Part 2 of this three-part series, Treesource will explore the ways to carefully use forests as carbon sinks while expanding timber harvests and the use of wood in built environments. What policies and investments can and should be made to create incentives for natural carbon storage?

“For the world to avoid ecological and social catastrophe, the scientists said, humans must quickly and radically transform the systems that provide energy –- by ceasing to burn fossil fuels.”

Don’t believe everything you read. It’s worth reading other perspectives, such as what you might see at: https://wattsupwiththat.com/ and https://www.youtube.com/c/TonyHeller

It’s great to promote forestry but we don’t need to become “climate alarmists” to promote forestry.

The quote is from the IPCC report and reflects the consensus of thousands of scientists involved in the preparation. I trust their assessment over bloggers that deny climate change is real.

John Tyndall a Physicist in 1859 definitively showed how CO2 and water vapor molecules serve to conserve heat, thus establishing the knowledge basis for the greenhouse effect that makes it possible for our planet to support the complexity of life forms we enjoy, including the wide array of forest ecosystems. Therefore the effect of increasing CO2 in the atmosphere has been understood and known to science for over 160 years. https://www.rigb.org/blog/2019/may/who-discovered-the-greenhouse-effect

Many of the predictions by the IPCC have been proven accurate over the past 20-30 years. To not heed their recent warnings seems foolish. The role of forests and wood products in addressing this global crisis is significant and important to communicate to people.

I’ve read everything you said many times in many places. But others don’t agree and they make a good case. It’s not too difficult to believe that this “climate problem” is exaggerated- but people who believe it seldom look at alternative views. I won’t bother to turn this into a lengthy debate but if you care to not be so focused on the prevailing view- you might start by looking at those links I gave. The skeptical case is actually very strong. The skeptics see this as a new religion with the same sort of blindness all religions are subject to.

“For example, the team assumed that all “natural forest management” lands would see a harvesting hiatus for 25 years. At the end of that period, the resulting larger-diameter trees would have stored more carbon – but also would provide more wood.”

Many forests are in poor condition. Putting off silviculture work in those stands just to store more carbon is a bad idea.

Joseph, I encourage you to re-read the article to put the quote you pulled out into context. The lead author acknowledged simplifying assumptions were made in order to conduct a national analysis and that each forest ecosystem needs to be assessed. He also acknowledged the need for “defensive carbon” management to reduced wildfire risk. The point made repeatedly by the various people quoted was, it is important to consider the local conditions and that in many instances the overall forest condition, health and resilience can be improved with appropriate treatments. Making your point that forest conditions can be improved and carbon offsets designed appropriately can help achieve that.

Here in Massachusetts, forestry leaders are now pushing the idea to put off harvests- they don’t say sometimes- and this ticks me off. Most forests here are in bad shape from past high grading. It’s as if they don’t even know what’s out there. But it’s more politically correct to talk about locking up carbon, blah, blah, blah (paraphrasing Greta Thunberg). In my opinion, as a forestry consultant for almost 50 years, forestry “leadership” are deeply out of touch- and that includes forestry academics. The sooner forests receive excellent silvicultural work- the better- which results in excellent economics, good for wildlife, good for aesthetics, and even good for carbon mgt., though I don’t believe there is a climate emergency.

Consider Katie Fernholz’s quote at the end supporting the notion that we can sequester more carbon and harvest more wood at the same time. We just have to apply the right practices. New England Forestry Foundation agrees with that approach and our modeling for New England indicates we can offset over 30% of emissions over the next 30 years through better forestry, continued harvesting and building with wood. This 30% solution is in line with the TNC national numbers and other studies soon to be released. It can be done in our forest types without a 25 year hold on harvests.

Robert that is good news you report. Can a link to the report be posted here so others can access that information? I suspect more specific regional analyses will show the potential for both more wood and more carbon in forests through forest management specific to the ecosystems of that region.

The statement made by Barry Ulrich of TNC “The challenge, of course, is how to grow more trees…” is not really the issue, and I think this is an important and often over looked distinction, the challenge is to grow more saw timber (till we get markets for low quality material that will go into long life products such as bio-plastic) at a quicker rate. This is easily accomplished with good silviculture and management and most likely could be done with shorter rotations, at least on industrial lands. Real goal is to produce as much lumber (the current product that goes into the longest lived products) as possible on an acre of land in the shortest time. It is well established that middle-aged forests (insert age range for your region but in New England is around 30-60 years) have the fastest growth rate and thus the fastest sequestration rate, while old forests (100 yrs+) the sequestration rate levels off and eventually declines. One caveat here is that one would need to grow the stand till the majority of the trees were of size to produce the desired longer lived products but, again for NE 80-100 years should be plenty long to achieve this maximization. The beauty of CLT and some other mass timber products is they can often use smaller pieces and some lower grade boards so smaller trees can produce these products which in turn are used for very long lived structures.

Another thing that is often left out (or under estimated) of these discussions and the climate calculations is the risk of large mortality events such as the increasing risk of hurricanes (again for NE is long over due) and other damaging storms and exotic pest outbreaks. Older forests, particularly unmanaged ones, are more susceptible to these and probably more importantly when these events occur in an old forest there is the chance for much more carbon to be released suddenly and many of the trees that could have gone into long lived products will be severely degraded if utilized at all.

I’m continually amazed at the emphasis on the carbon storage end (even among foresters and other natural resource professionals) when what we really need to do to reduce atmospheric carbon is increase sequestration and slow emissions. I know the carbon cycle is very complex, and you need to consider transportation and manufacturing emissions, but bottom line every gallon of oil that isn’t consumed is keeping carbon that would not be released otherwise ever, out of our atmosphere. That is what needs to be achieved.