A new study of tree populations in the continental United States, published this month in Science Advances, pokes at the conventional wisdom about climate change and its effect on forests.

While ecologists have generally believed that cold-adapted species will survive the planet’s warming by moving farther north and higher in elevation, the study by scientists at Purdue and North Carolina State universities showed they’re also migrating west.

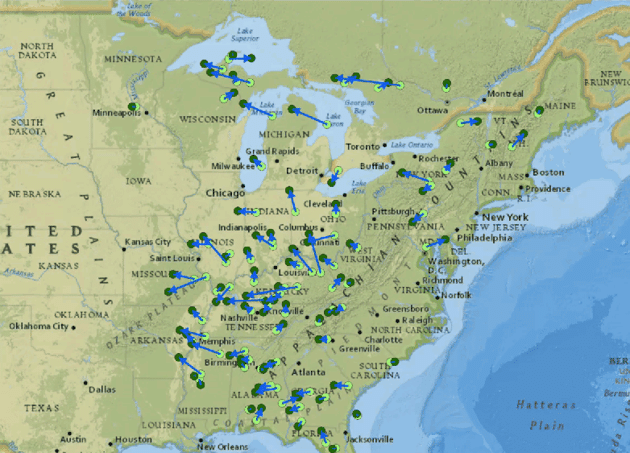

Using data from the U.S. Forest Service’s Inventory and Analysis program, reearchers mapped the distribution of 86 tree species common to eastern U.S. forests, including sugar maple, white oaks and American hollies.

Over the last 30 years, 73 percent of those species shifted their so-called “abundance centers” to the west, of which 65 percent were significantly significant. Meanwhile, 62 percent of the species migrated poleward, of which 55 percent were statistically significant.

The scientists were surprised, and said so in their first report on the analysis.

The results are fascinating in part because they don’t immediately make sense,” wrote Robinson Meyer in The Atlantic. “But the team has a hypothesis: While climate change has elevated temperatures across the eastern United States, it has significantly altered rainfall totals. The northeast has gotten a little more rain since 1980 than it did during the proceeding century, while the southeast has gotten much less rain. The Great Plains, especially in Oklahoma and Kansas, get much more than historically normal.”

“Different species are responding to climate change differently. Most of the broad-leaf species—deciduous trees—are following moisture moving westward. The evergreen trees—the needle species—are primarily moving northward,” said Songlin Fei, a professor of forestry at Purdue and one of the authors of the study, told Meyer.

“There are a patchwork of other forces which could cause tree populations to shift west, though,” Meyer continued. “Changes in land use, wildfire frequency, and the arrival of pests and blights could be shifting the population. So might the success of conservation efforts. But Fei and his colleagues argue that at least 20 percent of the change in population area is driven by changes in precipitation, which are heavily influenced by human-caused climate change.”

There’s a wealth of information to consider in the report. Here’s a link to the full account in Science Advances, and a link to The Atlantic’s story for a more general audience.

The upshot, of course, is that climate change will likely continue to surprise scientists as it unfolds.

Leave a Reply