Of the dozens of wildfires that burned across the southeastern United States last November and December, none was more devastating than the Chimney Tops 2 Fire in Tennessee.

Fanned by strong winds on the afternoon of Nov. 28, the fire grew to more than 17,000 acres, leaving Great Smoky Mountains National Park and raging through the city of Gatlinburg.

Fourteen people were killed, 145 were injured; 1,711 residences and 42 commercial properties were destroyed in Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge and the surrounding area.

On Dec. 7, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, Sevier County Sheriff’s Office, National Park Service, and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives announced the arrests of two teenagers in connection with the fire and the filing of a petition in a juvenile court charging them with aggravated arson.

The fire started on Nov. 23 in a remote part of the national park; steep terrain made firefighting difficult. Dramatic changes in the weather hampered firefighting efforts as well, and ultimately caused the fire to blow up.

Beginning on Nov. 27, a cold front brought unusually strong winds and tornadoes to eastern Tennessee. Great Smoky Mountains National Park officials reported wind gusts of more than 80 miles per hour, along with low relative humidity and fuel moisture, and several tornadoes touched down in southeastern Tennessee on Nov. 29.

With forests parched by months of drought, the fire spread rapidly toward Gatlinburg, igniting numerous spot fires in and adjacent to the park. Thousands of people evacuated from Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge and other nearby communities and resort areas as the fire swept north, but many others did not see the danger headed their way.

Nathan Waters, an assistant district forester with the Tennessee Division of Forestry, worked with a division crew and crews from Oregon and Alaska to protect homes between the park and Gatlinburg.

“The winds weren’t that bad when we got there, maybe 5 or 10 miles an hour. But then it really picked up — 50, 60 miles an hour, and trees were coming down in the woods,” said Waters. “I pulled the crews off the line, and we gathered at a park, and that’s when the winds began to shift. It was blowing the opposite direction than it had been blowing. The fire grew all of a sudden, and embers blew for miles and spread fires everywhere.”

Waters and the crews cleared debris from around as many homes as they could safely reach and started a backfire to prevent the main fire from reaching them. He noted that steep, narrow roads made access to many areas difficult.

In some areas, invasive plants complicated the firefighting effort. Near a hotel, Waters said, “there was at least four or five acres of kudzu in front of it, and it was browning, but not completely brown yet. But because we hadn’t had rain in so long, it was crispy dry. There wasn’t anything we could do with that kudzu. It was consumed so fast, and it threw a lot of embers.”

Railroad ties used in landscaping and as foundations for driveways burned intensely during the firefight, and some were still smoldering even after the area received several inches of rain, Waters said.

With dry conditions throughout the Southeast, numerous fires grew to thousands of acres each, such as the Rough Ridge Fire (27,870 acres) on the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forests in Georgia; the Rock Mountain Fire (24,725 acres) in Georgia and North Carolina; the Mount Pleasant Fire (11,229 acres) on the George Washington and Jefferson national forests in Virginia; and the Nolansburg Fire (7,400 acres) in Kentucky.

In Tennessee, dry conditions led Gov. Bill Haslam and Great Smoky Mountains National Park officials to issue burn bans, including campfires, in mid-November. The ban was lifted Dec. 7 in four counties in southeastern Tennessee to aid in efforts to clear tornado debris.

**

That the southeastern United States is undergoing a significant drought is not news to anyone who lives there.

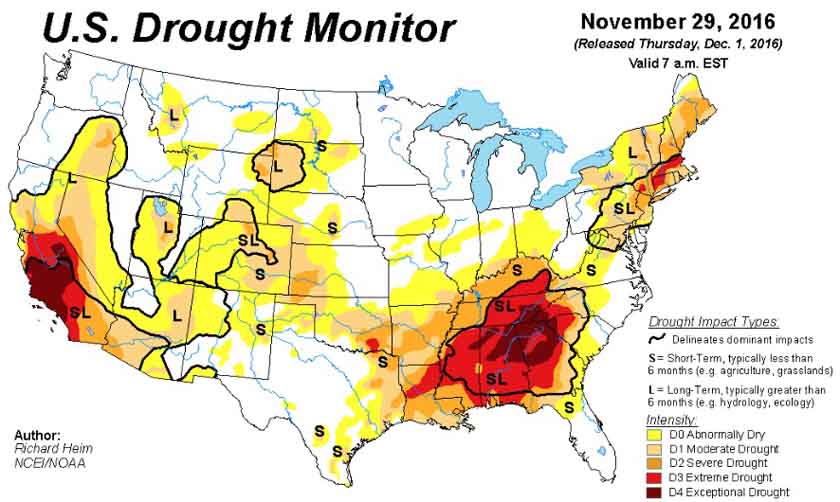

In late November, a portion of every state in the region was classified as being in an extreme or exceptional drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, a partnership between the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and NOAA.

The entire state of Tennessee was in a moderate to exceptional drought; more than 60 percent of the state was classified as being in an extreme or exceptional drought. All of Kentucky was experiencing moderate to exceptional drought, with nearly 25 percent of the state in extreme or exceptional drought.

“Extreme to exceptional drought covered about 97 percent of Alabama, 62 percent of Georgia, 21 percent of South Carolina, and 13 percent of North Carolina,” said Jordan McLeod, regional climatologist at the Southeast Regional Climate Center, an arm of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Such severe and widespread drought conditions hadn’t been seen since 2008.

“We’ve had some exceptionally long periods with no rainfall for many weather stations across the region,” McLeod said. “A station at the Eufaula National Wildlife Refuge in Alabama recorded 91 consecutive days without any measurable precipitation. That was the longest streak for any weather station in Alabama’s historical record.”

“Thank goodness that we finally got some beneficial rains at the end of November,” he added.

Precipitation amounts ranged from two to eight inches across most of Tennessee by Dec. 6, and about two to four inches in southeast Kentucky. Up to 10 inches or more fell in extreme southwest Louisiana and nearby parts of the Texas coast, and in the area where the states of Alabama, Georgia, and northern Florida meet, according to the Drought Monitor.

By Dec. 6, the severity of the drought in the Southeast was much reduced, although large portions of Alabama and Georgia remained in extreme and exceptional drought.

The damage, though, remained, and the scars will be visible for a generation to come.

This article originally appeared in The Forestry Source, a publication of the Society of American Foresters.

Leave a Reply