1. How forested is the United States? Here’s a surprising fact about our increasingly urbanized nation: About one-third of it is forested. Forests have an enormous impact on our water resources, economy, wildlife, recreational activities and cultural fabric. They also are major economic assets: The forest products industry manufactures more than US$200 billion worth of products yearly, and is one of the top 10 manufacturing employers in 47 states.

1. How forested is the United States? Here’s a surprising fact about our increasingly urbanized nation: About one-third of it is forested. Forests have an enormous impact on our water resources, economy, wildlife, recreational activities and cultural fabric. They also are major economic assets: The forest products industry manufactures more than US$200 billion worth of products yearly, and is one of the top 10 manufacturing employers in 47 states.

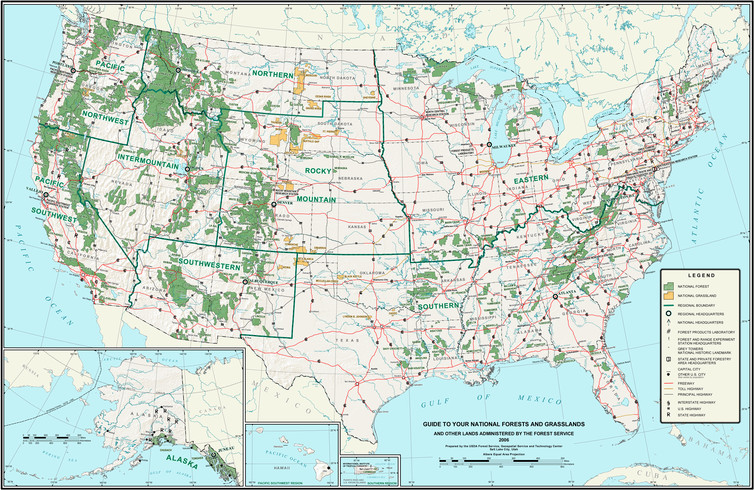

2. Who owns U.S forests? About 58 percent of the nation’s forestland is privately owned, mostly by families and other individuals. The public owns the rest. About three-quarters of the public forestland is owned by the federal government, mostly in national forests, with the rest controlled by states, counties and local governments. Forests in the eastern United States are mostly private; in the West, they are mostly public.

National forests were created to protect our watersheds and timber supply. Much of the water that ends up in rivers, streams and lakes comes from forested watersheds that filter the water naturally as it flows through. Forests also help control soil erosion by slowing the rate at which water enters streams.

Environmental pressure has caused timber production to become less of a priority in national forests. Since 1960, national forests have been managed under multiple use policy, which calls for balancing timber yield with other values like wildlife, recreation, soil and water conservation, aesthetics, grazing and wilderness protection.

3. How are forests regulated? The U.S. Forest Service is the largest agency within the Department of Agriculture, with a $6 billion budget and 35,000 employees. It manages 193 million acres of national forests and grasslands – an area equivalent to that of the state of Texas – spread across 44 states and Puerto Rico.

Starting in the 1970s, laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act created a new regulatory environment for forestry. As an example, listing northern spotted owls in the West and red-cockaded woodpeckers in the South as endangered species had major impacts on timber production because the law requires land managers to identify and protect “critical habitat” for listed species.

Government policies also affect private forests. The federal tax code provides for capital gains treatment for timber, allowing income from timber sales to be taxed at lower rates. Almost all states have a property tax classification program to encourage active forest management. Most of them value forestland based on its current use when they assess it, rather than its potential value if it were developed, as a way to keep trees on land.

4. Are any national forests still in their natural state? Yes. Congress can designate wilderness areas in national forests, national parks and other public lands. Road-building and other development are barred in these areas, but they are open for hiking and camping. There are 37 million acres of wilderness areas in national forests.

Wilderness designation offers a high level of environmental protection, but it also can cause resentment. Barring timber harvesting and mining and restricting recreational activities (for example, prohibiting off-road vehicles) can affect the economies of nearby communities. Debates about wilderness protection are part of a broader, long-standing controversy over federal control of land in the West.

5. What are the most serious stresses on U.S. forests? Climate change, insect infestations and decreased logging in national forests are making wildfires larger and more frequent. The Forest Service currently spends more than half of its budget on controlling wildfires.

For family forest owners, parcelization and fragmentation are major issues. Forestlands are being broken into smaller and smaller tracts over time, which can impact forest management, wildlife populations and water quality. One in six family forest owners plans to sell or transfer his or her forestland in the next five years, and smaller forests are likely to result. Owners of smaller tracts are less likely to produce timber or actively manage their forest.

In my home state of South Carolina, the forest industry used to own 2.7 million acres of timberland. Today it owns 170,000 acres, controlled mainly by timberland investment groups and real estate investment trusts. They manage it well, but they also tend to buy and sell it on a regular basis, and often chop off parcels that are better suited for development.

6. How may forests fare under the Trump administration? The new administration has a clear utilitarian focus, so I expect it to encourage land use and development. Wilderness areas are also likely to be an area of contention. If Congress amends major laws such as the Endangered Species Act, it could affect forest management.

Changes in the tax code or in cost-share programs that encourage reforestation and forest management could impact private forests, especially family forests. Investing in rural infrastructure, which was one of Trump’s campaign priorities, could benefit private forests.

Conservation groups are worried that Sonny Perdue, President Trump’s nominee for secretary of agriculture, may increase logging in national forests and has questioned mainstream climate science. As governor of Georgia, a major timber state, Perdue supported commercial timber harvesting. At USDA he will choose deputies to oversee the Forest Service.

President Trump’s first budget proposal proposes a 21 percent cut in USDA’s funding, including unspecified cuts to the national forest system, although it also pledges to maintain full funding for wildland firefighting.

is a professor of Forestry and Environmental Conservation (Forest Resource Management and Economics), Clemson University. This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

Leave a Reply