On Nov. 28, 2016, the unthinkable happened. A human-set wildfire on a remote, rocky mountain called Chimney Top in Great Smoky Mountains National Park began what can only be described as an unprecedented northward race that lasted several hours but covered 5.5 miles, until eventually reaching the border of the national park.

Unfortunately, this particular portion of the park border happened to be occupied by the scenic mountain village and well-known tourist destination and ski resort of Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Beginning at 5 p.m., the wildfire marched uncontrolled through and around Gatlinburg, burning more than 1,700 structures, including private residences, businesses, resorts and churches.

But the wildfire did not stop in Gatlinburg.

The fire jumped farther northward, burning the landscape around the scenic parkway that led to Pigeon Forge, home of Dollywood family amusement park. Neighborhoods along the southern periphery of Pigeon Forge were all but consumed, adding another 300 structures to the total.

The final toll of the 2016 Gatlinburg wildfire and other nearby fires was more than 2,400 buildings destroyed and 14 lives lost, with some estimates of damage by insurance companies totaling more than $500 million to date. Some insurance experts are predicting that the covered costs of the damage from this wildfire could rival the still-increasing recovery costs associated with Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Why was this wildfire so unusual?

The wildfire started on Nov. 23 on the south slope of Chimney Top, a well-known hiking trail destination for visitors to the national park. For three days, an inversion kept the wildfire fairly localized due to cooler temperatures and higher humidity near the ground surface, which also created a fairly stable atmosphere and little chance for fire growth.

By Nov. 26, the fire had reached only about six acres in size. This was nothing to worry about, because such innocuous fires are fairly commonplace in the park. On Nov. 27, however, the inversion lifted, bringing warmer temperatures, lower humidity and a more unstable atmosphere, which caused the fire to expand to 35 acres.

At this point, visitors to the park took notice of the wildfire and the large amount of smoke being produced, and users of social media were soon posting photos of the wildfire. An incident management team brought in three helicopters to begin bucket drops, but they had to fly considerable distances to find water sources, and this eventually proved ineffective at preventing the spread of the wildfire.

An order also was placed to bring in firefighters and engines to begin attempts at containing the wildfire. By nightfall, the wildfire was still within the containment area, still so uneventful and unspectacular that no firefighting staff was charged with monitoring the wildfire overnight.

Then things changed again.

On the morning of Nov. 28, the wildfire was still in this more remote location of the park, although it had spotted outside the containment area a half mile to one mile to the north. The incident management team took action. Firefighters and engines were sent to protect structures within the park in close proximity to the wildfire. Nearby fire departments outside the park were alerted to monitor for additional spot fires and wind-blown embers. Air support was suspended because of increasing winds and poor visibility.

But the real danger was fast approaching in the form of a weather system from the west, and with this weather system would come a shift to southerly, warmer, drier winds with wind speeds predicted to be 40 to 50 mph.

Between noon and 1 p.m. on Nov. 28, the winds had shifted direction and increased dramatically in speed, causing the wildfire to literally race northward downslope toward Gatlinburg, following the Newfound Gap Road (Highway 441). The fire soon reached the Twin Creeks area of the national park, just 1.5 miles from Gatlinburg.

By 5 p.m., the fire had reached the southern city limits of Gatlinburg near Minatt Park. Within the next hour, homes and businesses began burning as the winds drove flames into the city, ultimately burning the slopes and neighborhoods to the east and west of downtown Gatlinburg.

Even by 8 p.m., however, many residents were still unaware the wildfire had reached the city. No evacuation warnings were sent by emergency personnel via television or cell phones, and residents soon found themselves opening their front doors only to be confronted with fast-moving flames that were already consuming their neighbors’ houses.

By 10:30 that evening, fires had erupted near Pigeon Forge and several other locations, again catching residents off guard. By about 2 a.m., as the weather system kept approaching, light rains began and would eventually help in containing the wildfire, but not until after 90 percent of Gatlinburg had been literally burned off the face of the Earth and 14 residents and visitors had lost their lives.

In total, more than 17,100 acres would be consumed by this one wildfire, an amount of acreage comparable to the total acres burned in the entire state of Tennessee during a more intense year of fires.

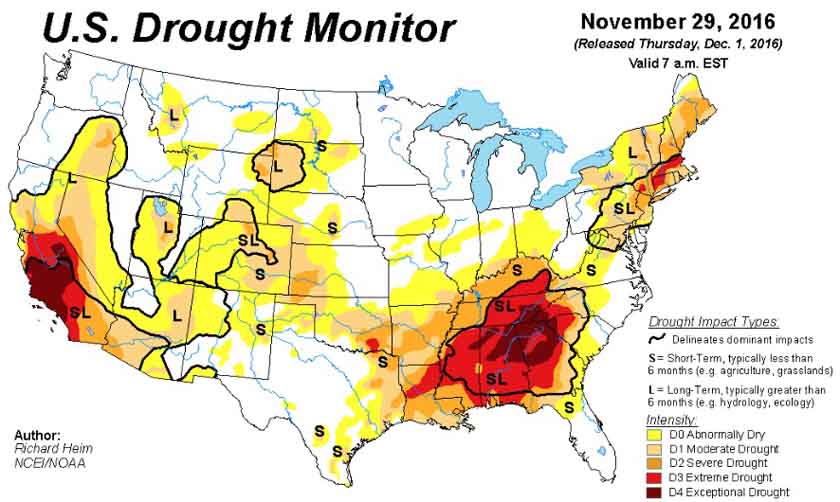

Drought was certainly a contributor to this high-intensity wildfire. Beginning in March 2016, the Southeast had seen one month after another with little rain and increasing drought conditions, which helped dry out fuels in all size classes. By September, wildfires were breaking out in many locations throughout the southeastern U.S., eventually burning a total of 119,000 acres across eight states.

By October 2016, the Southeast was in “exceptional” drought conditions, with a drought index of -3.8. By November, the drought index had precipitously dropped to -4.06, but drought experts also knew that worse droughts had occurred as recently as 2007 and 2008 in the Southeast, with even lower drought index values (e.g., -5.15 in November 2007).

Curiously, the fall fire season in 2007 was not particularly noteworthy. Southeastern forests also have a reputation among fire experts as being fairly resistant to high-intensity wildfires because of the generally wetter conditions and prevalence of what many call “temperate rainforests” in the national park. No one could have predicted the speed and intensity with which the Gatlinburg wildfire spread. This wildfire literally caught everyone, including the expert fire ecologists and highly trained firefighting incident teams, by surprise. In the short-term picture, little could have been done to prevent this level of destruction.

Future WUI Fires

But what about the long-term picture?

Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge exist in what is perhaps the best example of the wildland-urban interface (WUI) in the southeastern United States. The city limits of Gatlinburg are literally bounded by the National Park Service’s Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In fact, Gatlinburg is nearly surrounded by the park, which means that the surrounding forests are replete with fuels ready to burn.

Residents of these two tourist destinations must understand that they are surrounded by forests that burned repeatedly up until the 1930s, when the park was established and fire suppression became the norm. These fires were ignited by both humans and lightning, but the conversion of more than 500,000 acres into a national park meant completely different fire management plans for these forests.

Because no widespread fires have occurred since the 1930s, the federal lands around Gatlinburg have had more than 80 years for fuels to build up on the forest floor, for trees to increase densities to unprecedented levels, and for flammable understory shrubs (such as rhododendron) to grow and expand spatially across all portions of the landscape.

What does this mean? It means that the wildland areas around these mountain villages are now more contiguous with fuels, both vertically and horizontally, stretching from the highest elevations of the park to its drier, lower elevations. This literally forms a direct line of fuels to the urban interfaces, what I call the “fuels railroad,” and with the right long-term climate conditions and the right short-term weather conditions, the urban areas at the interface will face increasing risks from wildfires.

Can anything be done in the meantime, before the next wildfire? (And yes, there will another wildfire in the near future.)

The people of Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge must become better educated about the risk of wildfire — as must the residents of other WUI communities throughout the region and the nation. The risk is real, and it is increasing with each year in which ever-warmer temperatures globally will contribute to drier fuels and longer fire seasons.

City planners and administrators should be thinking about changing building codes and teaching the public better ways for living in a fire-prone landscape. Unless this happens, both towns will continue to build structures close together — I call them “fire dominoes.” The homes and businesses will be rebuilt with the same flammable wooden materials as before, whereas fire-resistant composite building materials are commonplace and strongly recommended.

Education is key here. Everyone must know more about the forests in which they live, play and work, and the role wildfire has played in them for millennia. Unless this happens, and happens soon, both Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge soon may see a repeat of what happened on Nov. 28, 2016.

Henri Grissino-Mayer is a professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Tennessee. His primary area of research involves studying the history of fire by examining fire scars on and in trees. This commentary was originally published in The Forestry Source.

Editor’s note: According to officials with Great Smoky Mountains National Park, an interagency review of the fire is under way and nearing completion. The review team will include representatives from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service (from outside of the GSMNP), and a local fire agency.

Leave a Reply