This photo essay includes eleven sets of photos documenting changes to specific sites in the Bridger-Teton National Forest.

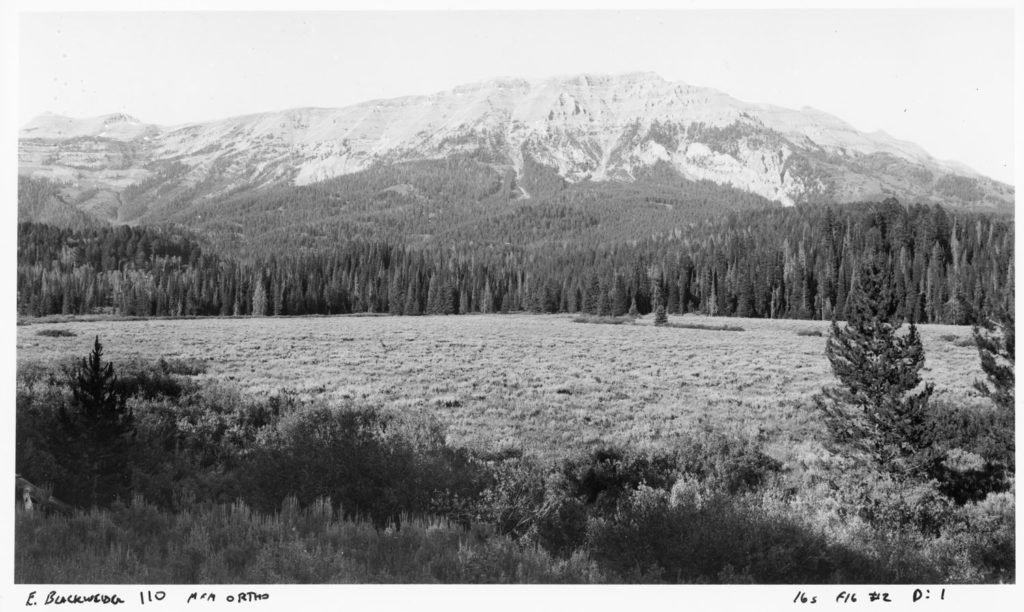

Image set 1: Eagle Peak and Tosi Ridge from Mill Creek

The view is to the northeast, and the photo point elevation is 7130 feet. The 2016 photo point is about 20 feet to the southwest of the original one, where most of the view was blocked by a few lodgepole pines.

The steep mountain front is along the Cache Creek fault, and the topographic relief from the valley floor to Tosi Ridge is about 4000 feet. This fault is due to mountain blocks colliding via compressional forces, with one block sliding over and above the other. The foreground terrain is the lower block, with stream-cut valleys, rather than the deep structural basins that occur when mountain blocks spread apart (e.g., the Teton fault, Range, and the Jackson Hole Basin). The low forested ridge beyond the plain is a glacial moraine. Sediment in melt-water emanating from the glacier, called outwash, formed the plain. Most of the ice flowed down the Dell Creek valley to the left of the scene, and the moraine at the far-left forms a divide that blocks modern streamflow from the larger Dell Creek valley, and isolates today’s Mill Creek compared to glacial times. The moraine and associated outwash plains are probably from the Bull Lake glacial stage, ending about 130 thousand years ago.

The historic Bellin Ranch was about a mile to the southwest of the photo point, and the ranch was operating during Blackwelder’s visit. The present and extensive Little Jenny Ranch is nearby, and some cattle grazing occurs along Dell Creek and within this scene as well.

The vegetation in the immediate foreground is dominated by a mixture of silver and mountain sagebrush, mountain snowberry, Kentucky bluegrass, mountain brome, and tall larkspur. At the near edge of the outwash plain, Booth willow, sticky geranium, meadow-rue, slender wheatgrass, and Kentucky bluegrass dominate. The outwash-plain vegetation is largely silver sage, shrubby cinquefoil, and mountain sage, with isolated patches of Booth willow along relic and active stream channels. The willows and channels are in the same locations today as they were a century ago, indicating very stable channel dynamics, and long-lived willows. Outwash soils tend to be course-textured, because the melt-water streams that form them sort out the fine sediments. In late summer, the soil is typically quite dry except near streams.

The herbaceous understory is diverse, and the most common species are silver lupine, Kentucky bluegrass, northern bedstraw, small-winged sedge, and yampa. Pocket gophers are a constant disturbance agent via herbivory and soil churning. The foreground trees are lodgepole pine, and the lower montane slopes and moraines have a mixture of subalpine fir, lodegpole pine, Engelmann spruce, and Douglas fir. Some of this area burned during the Cliff Creek fire in 2016 after this photo was taken.

Eagle Peak and Tosi Ridge from Mill Creek, 1911

Eagle Peak and Tosi Ridge from Mill Creek, 2016

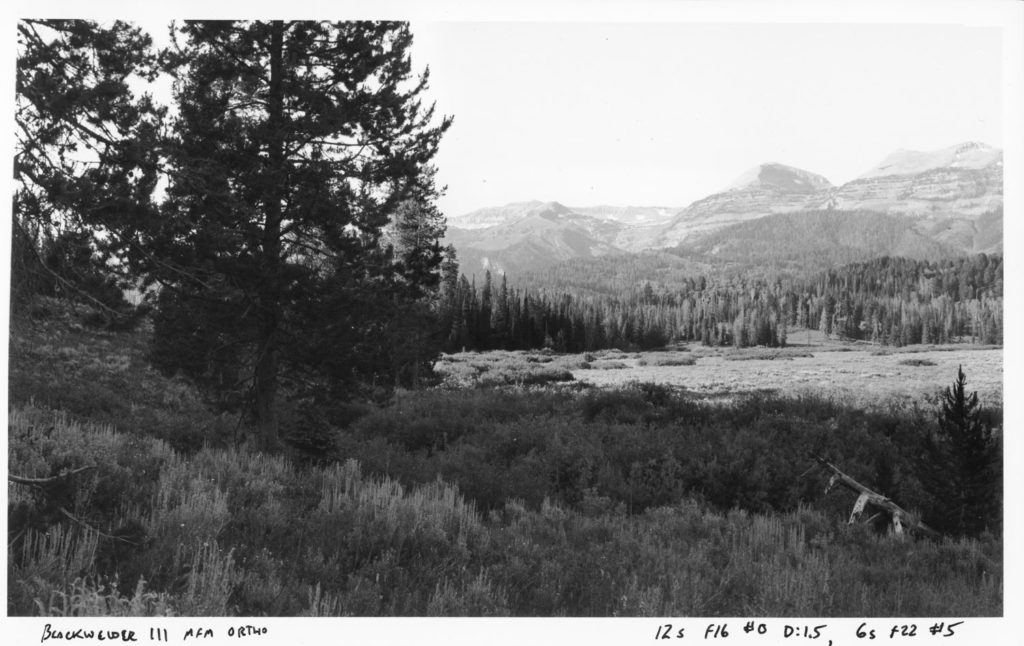

Image set 2: Hodge’s and Doubletop Peaks, as seen from the south from near Bellin’s Ranch

The view is to the north, and the photo point is the same one as for Blackwelder 110. The two scenes form a panorama, overlapping on Eagle Peak at the far right in this scene. Beyond the outwash plain, the gently-sloping mountain block buts against the steep, higher block beyond it — the highest ridge in the Gros Ventre mountains. Although the terrain looks continuous, there is a distinct difference in rock age along the Cache Creek fault here, and the youngest rock in the high block is about 200 million years older than the oldest rock in the lower one. The glaciated terrain of upper Dell Creek is prominent in the 1911 scene, and valley glaciers that flowed down Dell Creek formed the moraines near the outwash plain.

In 1911, the higher peaks had more snow than they did in 2016. Doubletop Peak, the highest one in the Gros Ventre mountains, is hidden behind the lodgepole pine in 2016’s foreground, and the downed snag at right was apparently the remains of the lodgepole pine there in 1911. The deep shadows in the foreground are from a coniferous forest, and shadow patterns indicate a denser forest in 2016. The time of photography for both years is within 10 minutes. The vegetation is similar to the neighboring scene.

Doubletop, Hodges, and Eagle Peaks from the south, 1911

Doubletop, Hodges, and Eagle Peaks from the south, 2016

Image set 3: Looking northwest into Granite Canyon from the moraine along Jack Pine Creek

The view is to the north, and the photo point elevation is 7300 feet. Granite Falls and hot springs are near the center of the 1911 image. Granite Creek is aptly named, as much of the canyon floor is littered with huge granite blocks dropped by the glacier that flowed down the canyon, although the source for most of this rock is the Gros Peak and Turquoise Lake area. Most of the granitic bedrock is below the canyon floor, and the surrounding peaks, as in the Swift Creek scene, are marine sediments. The foreground slope is part of a very high glacial moraine. Ice-dropped stones at the head of Jack Pine Creek, at 7800 feet, indicate that the crest of the moraine stood about 1000 feet above the Granite Creek valley floor. For this region, 1000 feet is an exceptionally large moraine thickness, so the moraine was likely draped over an existing ridge of unknown topography.

In 1911, the foreground vegetation is mostly mule’s-ears. Many range managers assume that dense patches of mule’s-ear indicate high grazing levels from sheep, that such patches are very persistent, and indicate clayey soils. The site is southerly and gravelly, and in 2016, the mule’s-ear was less common than in 1911. The dominant shrub is mountain sagebrush. This part of the Gros Ventre mountains had no recorded sheep grazing, and there was probably little to no livestock grazing here, including cattle, by 1911. Therefore, dense patches of mule’s-ears could be natural, and in this case, are not persistent as dense patches on the century scale. In 1911, the conifers just beyond the man and his horse are subalpine fir, Douglas fir, and lodgepole pine, and appear to be about 30 years old; the species mix is similar in 2016, and the trees probably established after the same fire evidenced in the Swift Creek scene (A. R. Schultz 58). This area burned in 2016 Cliff Creek fire, some weeks after the photo was taken. Understory forest vegetation here (e.g., buffalo berry, birch-leaf spiraea, lovage, Engelmann aster, Virginia wildrye) indicates that soils, via the glacier, were derived from mostly marine sedimentary rock.

Looking northwest into Granite Canyon from the moraine along Jack Pine Creek, 1911

Looking northwest into Granite Canyon from the moraine along Jack Pine Creek, 2016

Image set 4: Dry Cottonwood Creek from the northeast

The view is southwest across the terraced valley of Dry Cottonwood Creek, with the southern slopes of the Gros Ventre mountains beyond. The photo point elevation is 8352 feet; it was somewhat higher in 1969 to see beyond the aspen in the foreground. The alluvial fan filling the lower valley is very large for such a small creek and drainage basin, and the fan is likely of glacial origin, from ice and its sediment load spilling over the Spread Creek divide from north. The post-glacial stream, with a much diminished sediment source, has cut a series of terraces in the fan. The terrain drained by Dry Cottonwood is largely sandstones, shales, and a conglomerate dominated by quartzite pebbles and cobbles.

In 1917, aspen is the dominant forest, with some conifer forest at the extreme left- and right-view. Subalpine fir is the dominant conifer, mixed with modest amounts if Engelmann spruce and lodgepole pine. Gruell (1980) dated fires scars in the area to about 1885, so the 1917 scene shows post-fire recovery. Vasey’s big sagebrush dominates the non-forested slopes and alluvial fan. By 1969, aspen stands on the distant slopes have diminished, revealing or replaced by sagebrush. The Dry Cottonwood fire (autumn 1991) burned a substantial part of this scene and beyond to the north, killing much of the mature aspen in the foreground. Within the burn in 2015, sagebrush cover was about 15%, which is about half of what a typical mature stand would have here. Mountain snowberry had similar cover to sagebrush. Grasses dominate, and include the typical mix of needle-and-thread (Letterman and Nelson), mountain and nodding bromes, Nevada bluegrass, blue wildrye, and prairie junegrass. Blue-bunch wheatgrass was scarce as expected at this elevation.

Dry Cottonwood Creek from the northeast, 1917

Dry Cottonwood Creek from the northeast, 1969

Dry Cottonwood Creek from the northeast, 2015

Image set 5: Gros Ventre River valley from the crest of Gray Hills near Dallas Lake

The crest at the photo point is 8010 feet, and the view is to the west. This reach of the Gros Ventre River is about ¾ of a mile below the upper Gros Ventre slide debris, which became active in 1908 and created Upper Slide Lake. Since then, small tributaries, colluvial slopes, and the river’s flood plain and low terraces supply sediment to the reach below here until the confluences of Slate and Crystal Creeks. Alkali Creek enters the river on the left, halfway-up the scene. Conifers (mostly Douglas fir) have increased on the north-east facing slopes at upper-left, especially on the drier sites on the lower slopes. Glacial drift dominates the upper left of the scene between Alkali Creek and the forested ridge beyond, and some conifers have established on mesic, north-east facing aspects here.

The lower half of the steep slopes of the Gray Hills, on the right, are comprised of marine shale and bentonite within the Mowry formation; the scattered boulders on the gentle lower slopes came from a sandstone member of the Frontier formation, which rests on the Mowry. Greasewood, a very unusual species on the northern Bridger-Teton National Forest, occurs on these lower slopes, reflecting the saline nature of the Mowry. Most of the conifers are limber pine, and the mature limber pine in the lower-right corner is not the young tree that is in the vicinity in the historic scene. The shrubs near and left of this tree are big sagebrush (ssp. tridentata), while the smaller shrubs and half-shrubs scattered along this slope are horesbrush, winterfat, green rabbitbrush, broom snakeweed, and wax current, while the herbs are dominated by Indian ricegrass, spike fescue, blue wildrye, one-flowered goldenweed, fringed sage, golden buckwheat, kentrophyta milkvetch, pulse milkvetch, bluebunch wheatgrass, bastard toadflax, and many-flowered phlox. On the river’s flood plain and low terrace, the dominant trees are blue spruce and narrowleaf cottonwood, with a shrub layer comprised of yellow willow, silverberry, and sandbar and Pacific willows. The stringers of spruce that established on the large point bar, to the right of the straight-stretch of road, are on a low terrace and were probably not dependent on stream deposition or erosion for establishment.

The 1902 edition of the Mt Leidy quadrangle shows a road all along the Gros Ventre valley. This road’s absence in the historic photo is the basis for the estimated year of Leek’s photograph.

Gros Ventre River valley from the crest of Gray Hills near Dallas Lake, circa 1899

Gros Ventre River valley from the crest of Gray Hills near Dallas Lake, 2016

Image set 6: Hoback River Canyon from near Stinking Springs

The view is east and upstream, showing the lower end of the canyon, which ends abruptly at the Hoback fault. Stinking Springs, a short distance west of the photo point, is along the fault line. The 2016 photo point, at 6220 feet, is slightly west of Leek’s due to extreme instability at that location in 2016. The cliffs are Madison limestone, which also forms the extensive, dry, and unstable scree fields below. The early scene shows evidence of recent fire. W. H. Jackson captured this scene from a location nearby in August 1878. It shows similar fire effects, and Gruell (1980) estimated an 1871 burn date. The Leek scene was chosen here over Jackson’s because much of Jackson’s is hidden by modern-day, large chokecherrys lining an old road cut. Conifers among the cliffs and scree are limber pine and Douglas fir, most of which escaped the fire, and like-wise for many of the blue spruce, Douglas fir, and limber pine along the river banks. A broad stand of what appears to be young aspen dominates the scree slope at left. Water birch is the dominant tall shrub along the river.

In the 2016 scene, conifers have increased along the river banks and the scree slopes. Narrowleaf cottonwood is more prevalent along the river and on the scree slope; it is possible that what looked like aspen in 1900 was actually cottonwood, which can grow on colluvial as well as the usual alluvial sites.

Hoback River Canyon from near Stinking Springs, circa 1900.

Hoback River Canyon from near Stinking Springs, 2016

Image set 7: Red Hills anticline from Russold Hill

The steep, south-facing slopes of the Red Hills anticline dominate the scene. The immediate foreground is along a crest of a glacial moraine (Bull Lake stage), at 7380 feet. Although scarce, granite in the moraine indicates a likely source at least 45 miles east, in the Wind River mountains, or 20 miles north, from Angle Mountain. Much of the bedrock in the Gros Ventre River valley is relatively soft and greatly modified by erosion, transport by glaciation, or massive landslides, but extensive slopes of distinct formations occur along the Gros Ventre River valley, and here the Chugwater dominates. Despite dramatic differences in rock type, vegetation is largely related to topography, via aspect and elevation. Some early range and wildlife managers did not appreciate the inherent low productivity of these sites, and attributed it to elk use in winter, and cattle grazing which was just beginning here a century ago.

Leek’s scene likely pre-dates the livestock era in the Gros Ventre valley, and may also represent historic, natural elk populations and their seasonal use of summer and winter ranges. The two modern scenes, in 1970 and 2016, show modest increases in conifers on the steep, dry slopes, and a dramatic increase in aspen, Douglas fir, and limber pine in the foreground. Foreground trees are on a northeast aspect, and windblown snow accumulates here and enhances site moisture. Forests are not new to the more favorable sites, as the recently burned mature forest in Leek’s scene indicates. Since then, conifers have increased on northerly aspects, much of it by 1970. The scattered trees on the Red Hills are limber pine, many of which were there over a century ago. Some aged, live trees nearby date to the early 1400’s (Wise 2010), demonstrating that fire is rarely hot enough to kill trees on the harsh, dry sites, and their sparseness through the ages points to infrequent regeneration.

Red Hills anticline from Russold Hill, circa 1900

Red Hills anticline from Russold Hill, 1970

Red Hills anticline from Russold Hill, 2015

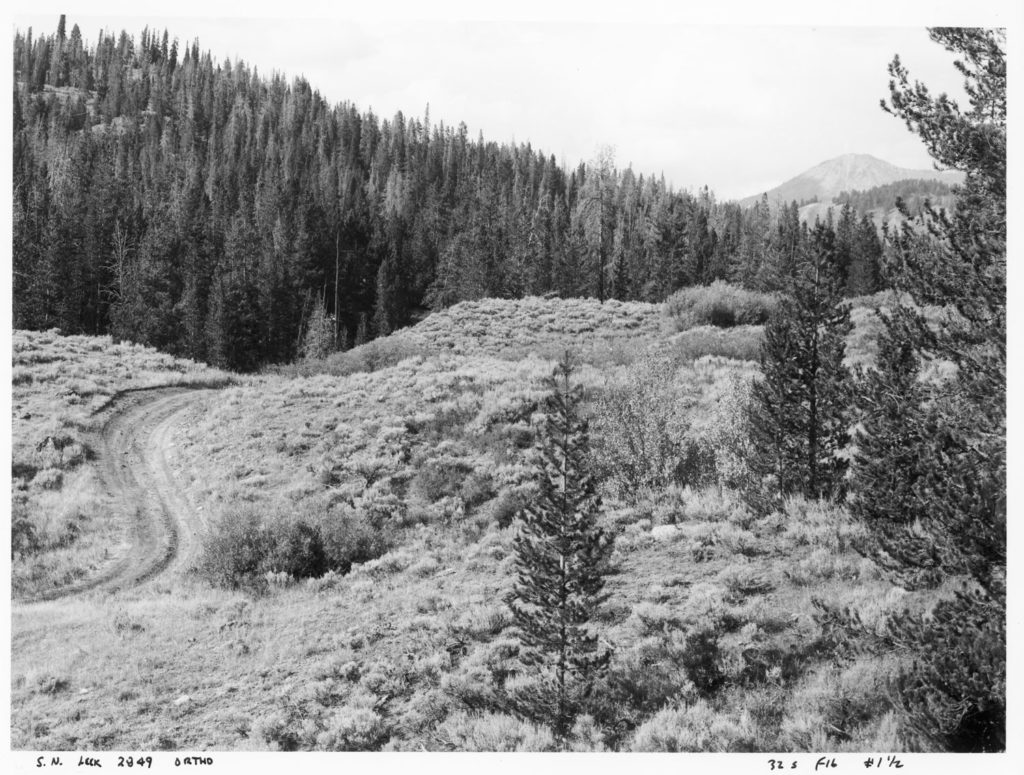

Image set 8: S. N. Leek hunting party crossing a slump in lower Slate Creek valley

Shales dominate the mis-named Slate Creek valley, and a very large landslide flowed into the valley just downstream from this view, taken from a steep hillside at 7380 feet. Slumps are common, but here it is the distinguishing feature. East Leidy Peak (10326 feet) is the prominent peak on the horizon. The view is to the northwest, and the distant hillside shows modest recovery from fire. Gruell (1980) estimated burn dates of 1842 and 1879. By 1970, mature lodgepole pine with some subalpine fir and Douglas fir dominate. Modest amounts of beetle kill shows in 2016.

In Leek’s scene, the foreground slopes show sparse big sagebrush (Vasey’s), shrubby cinquefoil, and substantially grazed grass and forbs. Leek was a prolific hunting guide, and considering the photo point location, and the prominence of the guided party, this was probably a carefully staged image. The antlers indicate autumn timing, but ungrazed grass would still be erect at this time, so cattle may have used this area by 1905, or the estimated date is later. The modern images show limited grazing, and there has been no cattle use since around 2000. The prominent trail in Leek’s scene may be due to hunting-party traffic, but cattle is the more likely agent. Most of the young pines in the 2016 scene were probably not present in 1970.

The modern foreground vegetation has substantially more shrubs, especially shrubby cinquefoil, which is generally unpalatable to cattle. Booth willow, in the saddle left of the upper horses, is not apparent in 1970 but reappears in 2016. In 2016, a prominent Geyer willow, to the right of where the upper horses were, is apparently new since 1970. Other photo sequences show that distinct, identifiable shrub willows can live over a century.

N. Leek hunting party crossing a slump in lower Slate Creek valley, circa 1905

S. N. Leek hunting party crossing a slump in lower Slate Creek valley, 1970

N. Leek hunting party crossing a slump in lower Slate Creek valley, 2016.

Image set 9: View south along the head of Pilgrim Creek near Wildcat Peak

The photo point, at 9480 feet, is near the crest of a steep ridge of Bacon Ridge sandstone, which overlies Cody shale. The shale is quite extensive, forming bench lands below the peaks with many small seeps, spring areas, and some small ponds. The headwater channels are stable in their dimensions, but lack of vegetation on their beds indicates active sediment transport. The 1928 scene shows more bare areas near the channels than in later years. This could be due to later snow melt in 1928 (there is a snow patch in Murie’s scene at the head of Rodent Creek). A short distance downstream, just beyond this scene, Pilgrim Creek drops steeply to the main stem, which is in the first valley beyond the ridge in mid-scene. The small landslide prominent at lower right in 1928 was revegetated in 1969, but since 1969, there appears to have been some re-activation. The bare slope in mid-scene, at the foot of the conifer slope, shows in 1928 and 2016, but it is in shadow in 1969 and less noticeable.

The herbaceous vegetation has been essentially stable since at least 1928, while conifers near the ridge top have died since 1969; most of the dead trees are whitebark pine. The other dominant conifer is subalpine fir. The Huck fire of 1988 burned near here but the only evidence within the scene are the subalpine fir snags at lower-right.

The gentle meadow slopes in the foreground are dominated by silver lupine, fern-leaf lovage, thick-leaved groundsel, thick-stemmed aster, and mountain brome. Within the gentle meadow, the smooth-appearing patches are seep-spring arnica, Lewis’ monkey flower, and small-wing sedge. The steep, sparser meadow at near-left is dominated by fern-leaf lovage and silver lupine.

In 2016, elk bedding areas and trails were common on the bench lands, but evidence of elk herbivory was low.

View south along the head of Pilgrim Creek near Wildcat Peak, 1928

View south along the head of Pilgrim Creek near Wildcat Peak, 1969

View south along the head of Pilgrim Creek near Wildcat Peak, 2016

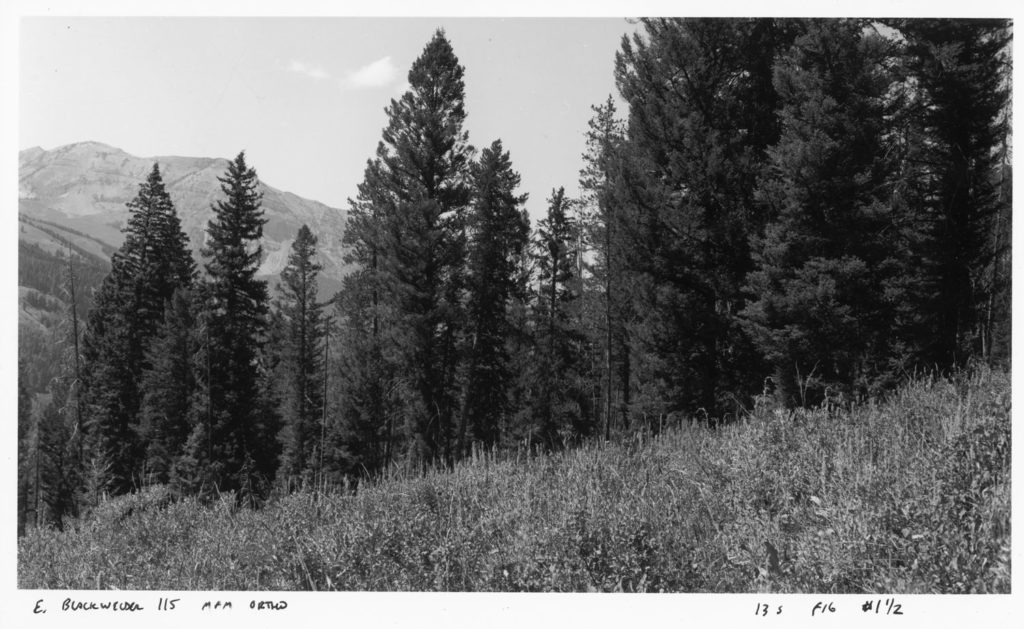

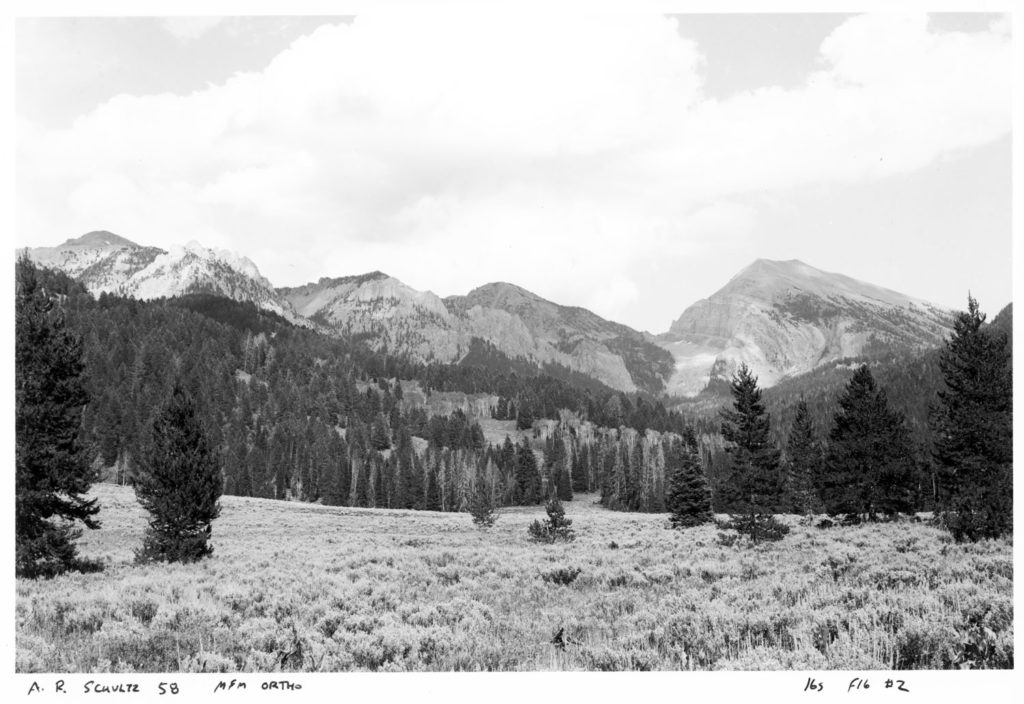

Image set 10: View east to Peak 11095 and environs from the Swift Creek fan near Granite Creek

The view is to the east, and the photo point elevation is 6820 feet. The foreground slope is a large post-glacial fan formed by Swift Creek and other nearby streams, which is perched on a terrace of the Granite Creek glacier’s melt-water stream (Bull Lake, 130K years BP). Several faults of various ages and types cross the southern part of the Gros Ventre mountains, but the high-mountain front here is mostly due to the Cache Creek fault. The high ridges are marine sediments, with limestone and dolomite forming the prominent cliffs. The folded rock beds on Peak 11095, at right, is the southerly-limb of an anticline (a sharp fold with the axis at the top, when intact), and this is what interested Schultz.

A sagebrush-grass community dominates the foreground, and lodgepole pine has increased in stature and density during the last century on the fan. In 1906, Douglas fir was quite prominent on the southwest-facing slopes, while the northwest-facing slope is dominated by young lodgepole pine; snags in 1906 indicate a mature forest before a recent forest fire. In 2016, the foothills have Douglas fir, subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, lodgepole pine and some quaking aspen. Aspen is more prominent in 1968, and it is less visible today due to their actual decline as well as taller conifers obscuring them. At the higher elevations, whitebark pine, or perhaps limber pine, is the predominant tree, and its cover has increased slightly on southerly aspects, and more substantially on northerly ones. Limber pine occurs across a large elevation range, and at high elevations, it can be more prevalent than whitebark pine on marine sediments. This is particularly so for the Teton Range, but whitebark pine can be abundant on marine sediments in the Gros Ventre mountains.

View east to Peak 11095 and environs from the Swift Creek fan near Granite Creek, 1906

View east to Peak 11095 and environs from the Swift Creek fan near Granite Creek, 1968

View east to Peak 11095 and environs from the Swift Creek fan near Granite Creek, 2016

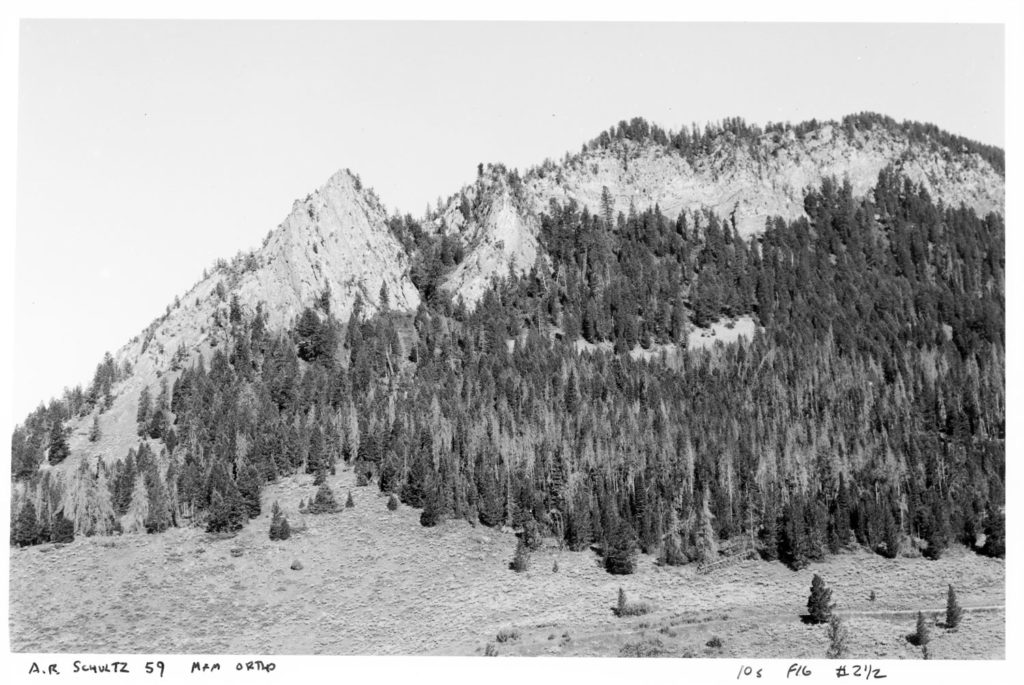

Image set 11: Sharp folds in Nugget sandstone near the mouth of Granite Creek

The colluvial slope, eroded from the Nugget sandstone cliffs above, faces southeast and support a mixture of conifers amid sagebrush and grass. The photo point, at 6460 feet, is across Granite Creek on a glacial terrace, paired with the one visible at the lower part of the scene.

In 1906, the triangular forest-patch with a smooth canopy is young lodgepole pine, perhaps 20 years old. Douglas fir, with the broader, darker crowns, dominates the cliff areas and the talus below the cliffs, while subalpine fir is scattered among the Douglas fir. The lower slopes have small patches of sagebrush, reflecting post-fire recovery.

In 2016, much of the lodegpole pine is beetle-killed, and Douglas fir and subalpine fir have increased within the lodgepole pine stand and elsewhere. On the lower slopes, sagebrush and mountain snowberry are the prominent shrubs, and have increased over the last century. The now coalesced forest patches are not contiguous with other forest patches in the area, and are largely surrounded by steep bed rock, thus reducing the prevalence of fire.

Sharp folds in Nugget sandstone near the mouth of Granite Creek, 1906

Sharp folds in Nugget sandstone near the mouth of Granite Creek, 2016

References:

- Gruell, G. E. 1980. Fire’s influence on wildlife habitat on the Bridger-Teton National Forest, Wyoming – volume I: Photographic record and analysis. USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Research Paper INT-235, 207 pp.

- Wise, E. K. 2010. Tree ring record of streamflow and drought in the upper Snake River. Water Resources Research Vol. 46, W11529. Supplementary data.

Leave a Reply