The fires in Yellowstone National Park began to burn in June 1988. A natural feature of the landscape, park managers expected the flames to fizzle by July, when rains historically drenched the forests and valleys of the world’s first national park.

But the rains never came. In unusually hot, dry and windy conditions, more fires erupted, spreading in and around the park until September. By then, 36 percent of Yellowstone was affected. Firefighting efforts topped $120 million.

Yellowstone experiences large fires every 100 to 300 years, and its flora and fauna are adapted to that schedule. Lodgepole pines like those at higher elevations in the park have pine cones that open in fire, releasing seeds to replenish a post-burn forest. But it takes time for trees to mature and the forests to recover — time that a changing climate has been depriving the forest of over the last three decades.

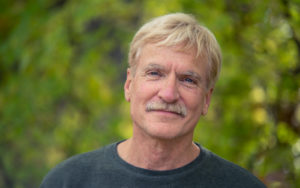

A new study published Jan. 17, 2019 in Ecological Monographs, led by Winslow Hansen and his former graduate adviser, University of Wisconsin–Madison Professor of Integrative Biology Monica Turner, shows that some of Yellowstone’s forests may now be at a tipping point. They could be replaced by grassland by the middle of this century.

“It’s terrifying in some ways,” Turner says. “We are not talking many years away. Today’s college students will be mid-career. It feels like the future is coming at us fast.”