In the end, the orange-coated Lorax protesting outside the 2018 International Mass Timber Conference was not the most surprising development that March morning in Portland, Oregon.

That came when I visited with the protest’s organizer and asked why Oregon Wild opposes the construction of mass timber buildings.

He explained: “We aren’t necessarily opposed to using wood, it can be good. We are opposed to how it is harvested. We are opposed to clearcuts.”

And then: “Recent research shows that the benefits of using wood compared to fossil fuel-intensive materials have been overestimated by an order of magnitude.”

Wow.

An error of 10 times is enormous in the research world. Being off by two times (or 100 percent) is large, but this would mean an error of 1,000 percent.

The protest leader’s statement came in stark contrast to the presentations inside the conference hall by architects, foresters, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) specialists and others.

While the protesters claimed the Lorax as an advocate for leaving trees in the forest to save the planet, those inside the hall advocated storing carbon in buildings in the form of wood products derived from sustainably managed forests.

The mass timber advocates spoke of planting and replacing the trees used in wooden high-rises. They spoke of saving the environment by avoiding the release of greenhouse gas emissions from the fossil carbon used to manufacture steel, concrete, brick and aluminum.

After the conference, I talked with Sean Stevens, executive director of Oregon Wild. He had attended the conference with a free pass provided by the event’s organizer, the Forest Business Network, to encourage dialogue between wood users, producers and the protesters.

Stevens repeated the assertion of the protest leader, which I learned they pulled from an academic paper published by researchers at Oregon State University and the University of Idaho. It was clearly an important sound bite for the group.

So too was this statement from the same report, which contended that mass timber buildings “are generally assumed to outlive their usefulness or be replaced within several decades.”

Now, based on the work of Law et al., Oregon Wild is advocating that storing more carbon in forests is better than using wood in buildings as a strategy to mitigate climate change.

People who are deeply invested in the well-being of their community and world often come to different conclusions about the best course of action.

But how could researchers come to such wildly different conclusions on the carbon effect of wood products? This led me to a series of interviews and multiple other sources to sort through a rabbit warren of questionable assumptions and conclusions in the OSU researchers’ paper.

To cut or not to cut?

Whether to sustainably cut forests is truly a global existential question. Earth’s growing population and the greenhouse gas emissions typical of modern life make our forest management choices critical to our climate change trajectory.

Forests have a phenomenal capacity to capture and store carbon for long periods of time. It is no idle question, then, to investigate whether it is more effective to leave forests alone to grow and store carbon, or to sustainably grow, harvest and use wood products in place of fossil fuel-intensive products like steel and concrete.

The research paper cited by Oregon Wild’s leaders was published by Beverly Law and others in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 2018. It examines different land use strategies to mitigate climate change in temperate forests.

The authors’ basic conclusion is this: By growing forests longer without cutting them, you can store more carbon. They propose doubling the rotation age from 40 years to 80 years on private lands, and halving the harvest on national forests in Oregon. They also suggest their approach can be applied to other temperate regions.

After its publication, the paper – and its call for no cutting – was the basis for a High Country News report, “Timber is Oregon’s biggest carbon polluter.”

But how did the OSU team reach their conclusion and why do other scientists strongly disagree? It boils down to whether they made reasonable assumptions.

The controversy – and the paper itself – demonstrates a divide among the science, environmental advocacy and conservation communities on the appropriate path forward for public policy.

Who should make policy decisions and what information should they be based on? We often look to scientific research to help sort through these issues.

And what do we do with science that seems contradictory? The High Country News story reported on the OSU researchers’ conclusions, but did not vet the claims with other scientists. And advocacy groups are now recommending policy changes based on the contested report and its findings.

Science is a process, not a result

Science isn’t flawless. It is a human institution and humans are flawed. We all have biases, both conscious and unconscious, which are woven into the fabric of our thought processes.

However, science has built-in processes to filter out human shortcomings. For example, international bodies collaborate to develop and critically review standardized procedures to remove as much of the personal biases as possible.

The scientific method requires authors to publish their methods so others can test them and replicate the results. The science community also uses reviews by anonymous peer experts so the reviewers are free to provide critiques and question authors without personal repercussions.

Science is an iterative, incremental learning process intended to be open and transparent. The goal is to reveal solid, factual information. Still, the journey toward that goal can be convoluted.

Social and psychological research shows that unconscious biases can creep into the thinking process in multiple ways. So another approach to sorting out apparently conflicting information, in addition to established scientific processes, is to apply Occam’s Razor, a principle from philosophy developed about 800 years ago.

It says: When there are two possible explanations, the simpler one is the more likely. Another way of saying it is: The more assumptions you must make, the more unlikely the explanation.

That brings us to the crux of the issue raised by the OSU scientists’ paper and Oregon Wild’s use of it: What is the balance between the sustainable harvest and use of wood to replace fossil fuel-intensive materials like steel, concrete, aluminum and brick versus leaving some forests untouched for long periods of time to store the carbon in live and dead trees?

Make assumptions with care

Did the scientific process break down in the review – or lack of review – given this paper and its assumptions and conclusions?

The problems that surfaced in the Law paper include:

- The quote used by Oregon Wild can’t be found in the references cited.

- The calculation used to justify doubling forest rotations assumes no leakage. Leakage is a carbon accounting term referring to the potential that if you delay cutting trees in one area, others might be cut somewhere else to replace the gap in wood production, reducing the supposed carbon benefit.

- The paper underestimates the amount of wildfire in the past and chose not to model increases in the amount of fire in the future driven by climate change.

- It assumes a 50-year half-life for buildings instead of the minimum 75 years the ASTM standard calls for, which reduces the researchers’ estimate of the carbon stored in buildings.

- It assumes a decline of substitution benefits, which other LCA scientists consider as permanent.

- It models just one species of insect to account for tree mortality when there are a variety of insect and diseases which impact forest carbon capture and storage. And the insect mortality modeled was unrealistic.

- The OSU scientists assumed wood energy production is for electricity production only. However, the most common energy systems in the wood products manufacturing sector are combined heat and power (CHP) or straight heat energy production (drying lumber or heat for processing energy) where the efficiency is often two to three times as great and thus provides much larger fossil fuel offsets than the modeling allows.

- The researchers claim to conduct a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), but fail to use the international standards for conducting such analyses, without explaining this difference in methods.

- The peer reviewers did not include an LCA expert.

- The claimed significance of substantial carbon savings from delaying harvest and the large emission numbers from the forest products sector are undermined by all of the above.

As part of the IMTC 18 conference, OSU professors hosted a tour of the new forestry building under construction using mass timber, where they indicated the powerful carbon benefits of using wood.

Dr. Maureen Puettmann, an LCA specialist, a courtesy faculty member at OSU and the director of operations with CORRIM, indicated multiple issues with the Law paper, many of which are included on the list above.

Trying to sort through the issue of quality control on research papers, I asked Dr. Anthony Davis, acting dean of the Oregon State University School of Forestry (the lead author’s home institution), how he resolves conflicting research results coming from within the same school.

Davis indicated: “It isn’t the role of the dean to resolve these differences, but rather to ensure that all of our faculty are able inform an ongoing dialogue through replicable research practices. Then, the peer-review process of scientific publications is critical to ensure that the assumptions made in a particular project are clearly stated and reasonable relative to the outcomes of that work.”

He added, “Researchers often explore extremes of a subject on purpose, to help define the edges of our understanding; or other studies might only examine one aspect of an issue which in reality does not occur in a vacuum. It is important to look at the whole array of research results around a subject rather than using those of a single study or publication as a conclusion to a field of study.”

The decision would be challenging enough if carbon were the only issue, but it isn’t.

There are myriad other benefits that forests provide society besides carbon. Water quality and quantity, places to recreate, balancing wildfire risks to lives, property and the diversity of habitat for animals are a few of the benefits to be considered.

In addition, the material for the cardboard boxes that deliver goods to our houses or the store where we shop, as well as the wood most of our homes are built from, come from forests.

Should the offices and manufacturing plants where we work be made of wood in the future? These various objectives can be in conflict with each other.

Davis, the acting OSU forestry dean, recognizes these complexities and encouraged me to visit directly with PNAS about their scholarly review process – and with Dr. Law and Dr. Harmon, the authors on OSU’s faculty. He said he would encourage them to visit with me.

Meanwhile, back at IMTC

The Occam’s razor answer to the carbon question was encapsulated by Alan Organschi, a practicing architect, a professor at Yale and one of the founders of TimberCity.org. He was among the presenters at IMTC 18.

When I asked about the benefits of substituting wood for steel or concrete and the variation in the magnitude of the benefits, Organschi emphasized that he isn’t an LCA specialist or scientist and then offered his thought process: “There is a huge net carbon benefit [from using wood] and enormous variability in the specific calculations of substitution benefits. We don’t have time to wait for precision, we have to use our best judgment.”

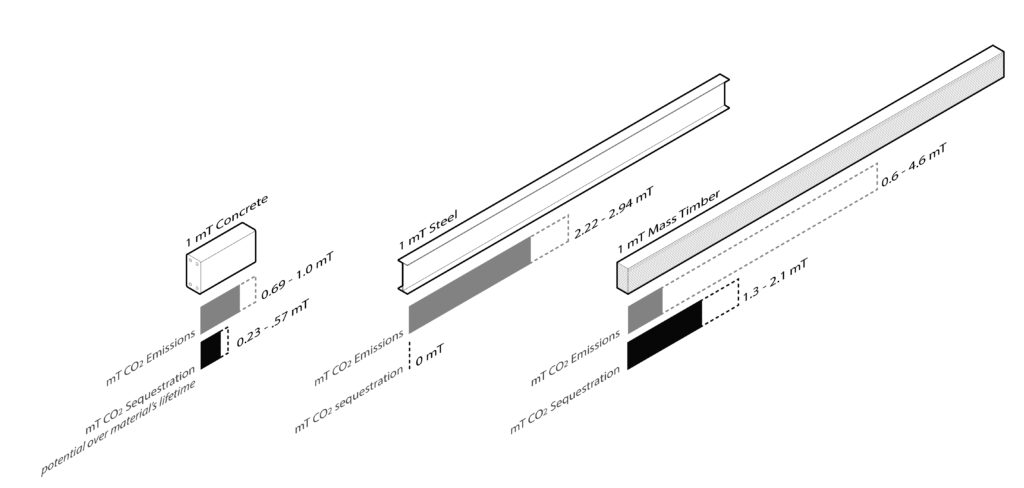

In the construction world, Organschi said, a ton of wood (which is half carbon) goes a lot farther than a ton of concrete, which releases significant amounts of carbon during a building’s construction.

And remember: We only have about 18 years to change our fossil energy use to avoid exceeding the 450 ppm of carbon in the atmosphere that would produce a 2-degree temperature increase.

Organschi went on to paraphrase Dr. James Hansen, the former NASA climate scientist who has been vocal about climate change since early in its research history. In the late 1980’s he said, “Quit using high fossil fuel materials and start using materials that sink carbon, that should be the principle for our decisions.”

For Organschi, the choice of wood is obvious.

In 2007, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) acknowledged the importance of sustainable forest management and wood products as essential to solving the carbon problem associated with climate change.In other words, if you don’t grow it, you mine it.

For a more complete analysis, see Treesource.org, an online periodical focused on forests.

[…] appreciative of David Atkins’ effort to delve into the complicated area of forest carbon in this piece at TreeSource. I actually asked several scientists if they knew of a paper that outlined the […]