SPRINGFIELD, Ore. – Mayor Christine Lundberg had the revolutionary idea: Take a banal urban edifice – a cement parking structure – and recast it as the catalyst that connects Springfield’s rich history with a forward-thinking future.

Her citizenry concurred, and now Springfield (population 60,000) plans to build a four-story parking structure out of cross-laminated timber (CLT).

Keep reading: They’re not crazy. It can be done. In fact, it is the backbone of a multi-pronged strategy to showcase sustainable design, grow jobs and improve high school graduation rates.

The garage will be the sole publicly owned building in the planned redevelopment of Glenwood (an incorporated area west of Springfield) along the Willamette River. The proposal also includes a hotel/conference center, commercial buildings, housing and parks.

Springfield’s school district saw opportunity in Lundberg’s idea as well. The educators want to improve student success and career readiness by capitalizing on the interest in mass timber and incorporating advanced manufacturing into the curriculum.

And Lundberg is just getting started.

Her mother’s moral compass

Springfield’s change-making mayor got an early start in politics. Her mother was an ardent supporter of the Kennedys – and, although too young to vote, Lundberg volunteered at two campaign stops for Bobby Kennedy.

“Two weeks later, he was shot in California,” she said. “This gave me the lasting impression that politics is volatile and painful.”

Lundberg’s mother was paralyzed from polio and confined to a wheelchair. Growing up helping her mother, she became inured to people staring at them and learned not worry about what others thought. Later, she joined the U.S. Navy and worked on fighter jets, where she was often the only woman working alongside 200 men.

She attributes her moral compass to her mother.

“My mother taught me a lot about the good and bad parts of society,” Lundberg said. “My interest in public service comes from her. She said you should give back to your community.”

Being comfortable in her own skin led to community service and, eventually, leadership. She was elected to the Springfield City Council in 1999, and is in her third and final term as mayor.

Sap in their veins

Lundberg envisions mass timber as the next evolution in her community’s natural resource economy.

“We have timber. It’s renewable, it’s sustainable, it’s climate friendly, it’s all of those things,” she said.

Springfield’s history is inextricably tied to timber.

“When I grew up here, almost every man in the community worked in timber,” the mayor said. “Even the guys in high school, they had summer jobs and they would be out in the woods logging. So they all smelled like fresh-cut wood.”

Like many Northwest timber towns, the 1980s were full-throttle production, but automation and declining federal harvests jammed the brakes in the ‘90s. Today, timber and wood products maintain a strong presence in Springfield. The economy, however, has diversified. Loaded log trucks now rumble past high-tech companies, craft breweries and a major medical center.

“There used to be more pride in the community,” said Vonnie Mikkelsen, president and CEO, Springfield Chamber of Commerce. “We had good-paying jobs and well-funded schools. We lost a lot of jobs in the last 25 years. That’s led to a loss of hope, of pride, a certain loss of identity, if you will.”

Added Lundberg: “The timber industry shrunk, but never left. We still make a wide array of products: structural lumber, glulam beams, paper, resin and secondary manufacturing. So if you go down A Street, you still see several mills. We never lost that foundation of wood and its significance for us.”

Springfield’s Eiffel Tower

Most demonstration projects set out to prove something can be done, so it can be replicated. The idea of building a CLT parking garage is unique. City planners don’t expect to build more — it’s one and done.

Like the Eiffel Tower, the structure will showcase the capability of the technology and push the boundaries of commercial applications. It will make a bold statement.

“Mayor Lundberg is doing something important for the pride of the community,” said Lech Muszynski, associate professor at Oregon State University. “She’s demonstrating the capacity of this technology. If it can work for this challenging open parking structure, it can work for just about anything else.”

Muszynski applauds the city’s efforts: “It’s in your face, right? It’s not somewhere in Portland. It is right here in the home of the industry, right when everybody thought it was dying.

“This is a message: We are very much alive, we are vibrant, innovative and modern. This is 21st century industry.”

Partnerships make it possible

Thumbing through a National Geographic, Lundberg flipped to a story featuring mass timber prophet Michael Green.

“Here’s an idea about using wood in a new way that is renewable, sustainable and sequesters carbon. How can you be against it?” she said.

Recognizing the infancy – but also the promise – of mass timber, the mayor wanted Springfield to develop “a signature project.”

“We have to build a parking structure in Glenwood (an incorporated area west of Springfield) to serve the hotel complex and redevelopment,” she thought. “It’s on the river, it’s beautiful. We should build it out of wood.”

Why not build a wooden skyscraper like those dotting the Portland skyline?

“Why would I pick the thing that we could do quickly?” Lundberg said. “No, I went right for the parking structure. I’m not sorry, because it is a signature piece that is forcing us to study the capabilities of using wood exposed to the elements.”

Weatherization and durability were just two of many design challenges. Springfield needed technical expertise, so reached out to the University of Oregon Architecture School and created a student design studio.

Judith Sheine’s department was already a leader in green building, so she wasn’t sure how students would react when she pitched the mass timber parking garage. The response? Overwhelming.

“It’s just still a little bit surreal, that there’s been so much interest in the parking garage,” Sheine said. “We weren’t sure that students would want to take it. And my colleague said the students were telling him, ‘It sounds really interesting.’ And he said, ‘Did you hear? You know that it’s a parking garage right?’ ”

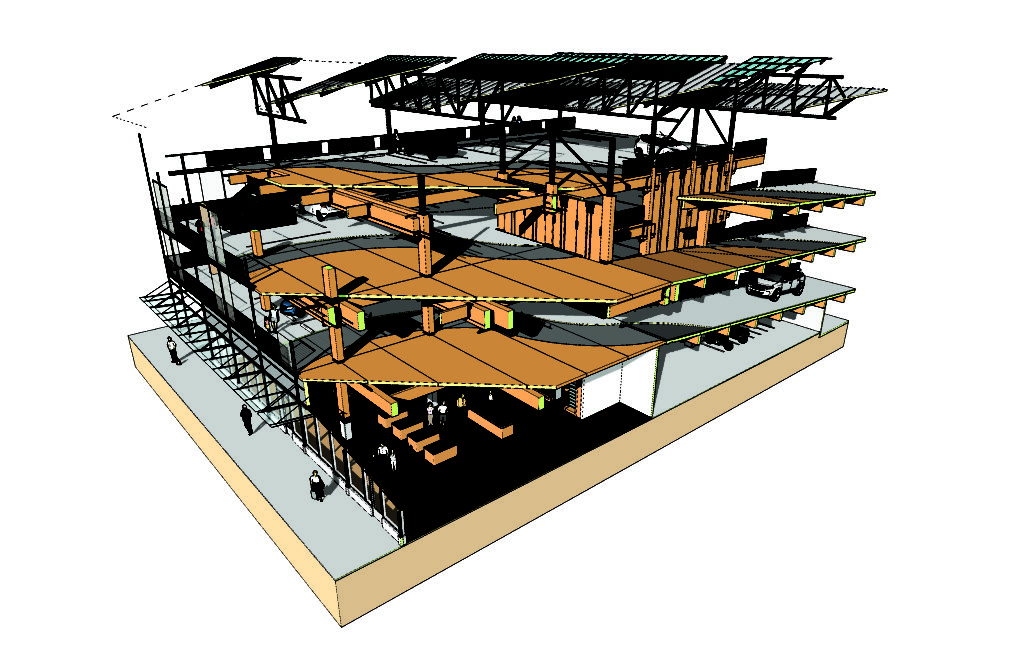

Under the supervision of Sheine and professor Mark Donofrio, nine student teams rolled up their sleeves and went to work. First, they verified that a CLT parking garage was structurally and architecturally feasible. That alone garnered Springfield recognition as a leader in the mass timber movement.

Springfield provides the spark

“I think Mayor Lundberg is being really smart about this,” Sheine said. “She says, ‘Look, this has value from an industrial standpoint. It could bring jobs back to Springfield. But it also has environmental benefits. If you have to build a parking garage, shouldn’t it be out of wood, rather than concrete and steel?’

“Springfield is a timber town. It’s part of their identity. They want this signature project, in this signature development, to honor that history. It reflects the culture of the place and the importance of sustainable design.”

The project won Oregon BEST’s CLT Design Contest and received $155,000 to fund research, performance testing and code documentation. (Oregon Built Environment and Sustainable Technology is a state agency that encourages environmentally friendly innovations.)

The newly minted National Center for Advanced Wood Products Manufacturing and Design (a partnership of OU’s architecture school and the colleges of forestry and engineering at Oregon State University) cosponsored the design contest and is overseeing the research and performance testing.

Already, Springfield’s innovation has sparked CLT design studios for two additional structures. OU architecture students recently completed designs for a mass timber version of the new Hayward Field West Grandstands on campus. And Lane County committed $50,000 to a mass timber design studio for its new courthouse in downtown Eugene.

In addition, the mayors of Springfield and Eugene have advocated that the University of Oregon build parts of its new $1 billion Knight Campus expansion from CLT and mass timber.

“We may be able to use CLT in some of the non-research spaces of the campus,” said Zack Barnett, the university’s director of digital communications. “University leadership has directed our architect to work with our School of Architecture to explore areas where CLT may be used.”

The devilish details

The city of Springfield used $670,000-plus in urban renewal funds to hire SRG Partnership to design the 214,000-square-foot garage. In addition, the firm has conducted rigorous due diligence testing to ensure the structure, when built, will remain standing for years to come.

“It can be done. Yes, absolutely,” said Lisa Petterson, a principal at SRG Partnership.

And can it be permitted?

“Both the fire marshal and the building official at the city of Springfield have been part of our design team,” said Peterson. “We haven’t dotted every “i”, crossed every “t” or submitted the paperwork yet, but no red flags have been raised.”

Still, significant challenges remain.

In the rain-soaked Northwest, any open-sided parking structure needs protection from moisture and the wear-and-tear of vehicles. SRG’s research and design team has scoured the globe for solutions, but has yet to settle on the best technology.

The goal is to design a system that protects the underlying CLT structural layer while preventing moisture from penetrating through the top layer. Promising options include a sheet membrane with concrete topping and a layered membrane with asphalt topping. Think of it as Gore-Tex for wood. The team will test the top candidates this summer in an advanced weathering chamber and asphalt lab.

“I wouldn’t call it a red flag, more of a yellow light — proceed with caution,” said Ethan Martin, regional director of WoodWorks, an organization that provides project assistance, education and resources related to the design of non-residential and multi-family wood buildings.

“You’ve got to protect it from water, oil and gas, and freeze-thaw,” Martin said. “I’m confident the city will have a great maintenance plan, but unfortunately the economy does what the economy does. Springfield, like many places, has experienced a few economic downturns. You own a piece of property and, all the sudden, your tax base isn’t what it used to be. You’ve got to figure out where to make cuts.”

His cautionary note underscores the risk Springfield’s leaders have shouldered. If you’re building the Northwest’s mass-timber Eiffel Tower, it had better hold up in the rain.

Low graduation rates and too few skilled workers

To Lundberg, the innovation of mass timber could spark young minds eager to solve real-world problems – like how to design Gor-Tex for wood. Nurture that curiosity and you prepare them for advanced careers in natural resource-related fields.

In doing so, you address two statewide problems – low high school graduation rates and a difficulty finding skilled workers for advanced manufacturing jobs.

Oregon public schools rank 48th in the nation in high school graduation rates. Locally, Springfield and Thurston high schools graduated 64 percent and 75 percent of their seniors in 2016.

However, Mikkelson, at the Springfield Chamber, sees an encouraging shift.

“Increasingly, local businesses want to be a part of this solution — they want to engage, to roll up their sleeves. We have businesses that are ready to give their time and their employees’ time to sit down with school district officials and talk solutions,” Mikkelson said.

Enter mass timber.

“I want Oregon jobs for Oregon kids,” said Lundberg. “We are surrounded by forests, but kids grow up disconnected from nature. I want them to think of the woods and ask what can I create with this that makes the world a better place.”

Springfield is building its first new middle school in 20 years – Hamlin Middle School, home of the Loggers. The structure has three large segments of CLT and dozens of beautiful wood beams and columns.

DR Johnson of Riddle manufactured the CLT panels. One CLT wall frames the “collaboration space” – a shared area that can be rearranged to fit different needs. Another wall defines the “maker space” for STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math), dedicated to hands-on learning.

The materials reflect the district’s intent to honor history while looking to the future. Elegant wood columns stand as clear reminders of the forest just outside the school walls. Thick beams cross wide spans, giving the impression of a canopy.

The exposed CLT walls, Lundberg said, “illustrate what is possible without compromising what is necessary.”

The CLT panels at Hamlin Middle School are the first use of mass timber in Lane County.

“A new generation of students is going to see wood products in the school,” the mayor said. “They’ll recognize that wood is a big part of who we are and what we can be. We hope to get the students excited and thinking about what wood can mean in their own lives, in their own education, their own career choices.”

An evolving identity

Here’s the myth of Springfield.

“When the Riverbend Hospital did not locate in Eugene, they were worried because all the children born would have Springfield on their birth certificate, as opposed to Eugene,” Lundberg said. “The myth is that we are a little bit of a second-class community.”

“I don’t know why people don’t see us,” she said. “And then, on the other hand, I have people who say, ‘I moved here specifically because I just like the way you do things. You get things done. You have this straightforward way. You make decisions and move on.’ ”

The real myth, then, is that cultural identity is static. The truth is that places – Springfield included – change and how we think of them must change as well.

Marcus Kauffman works for the Oregon Department of Forestry. A longtime Oregonian, he specializes in biomass and other market-based solutions to natural resource challenges.

[…] MARCUS KAUFFMAN – TREESOURCE · Image by TOM WADDELL / FOREST BUSINESS […]