As nations across the world scramble to identify and implement strategies for stifling climate change, a new study finds improved land stewardship presents an undervalued avenue for both storing and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

As nations across the world scramble to identify and implement strategies for stifling climate change, a new study finds improved land stewardship presents an undervalued avenue for both storing and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

A team of scientists finds that updated land management practices could bolster international efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while also meeting the global demand for food and fiber, the researchers report Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

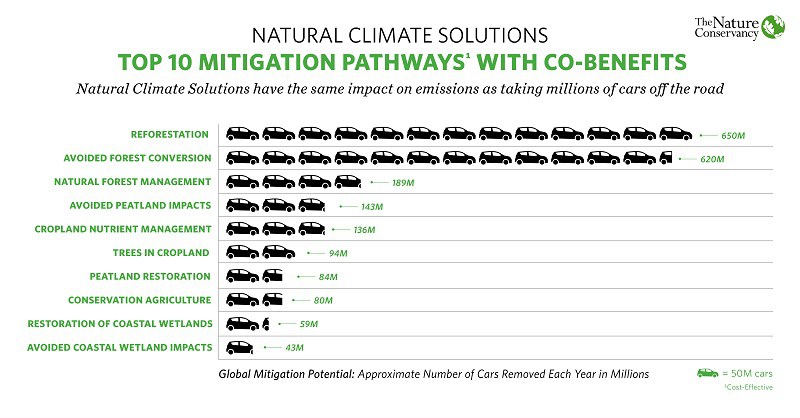

The team’s findings suggest that natural climate solutions, as outlined by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change, can be expanded significantly by programs that focus on the large-scale protection and restoration of forests, farmland and grasslands.

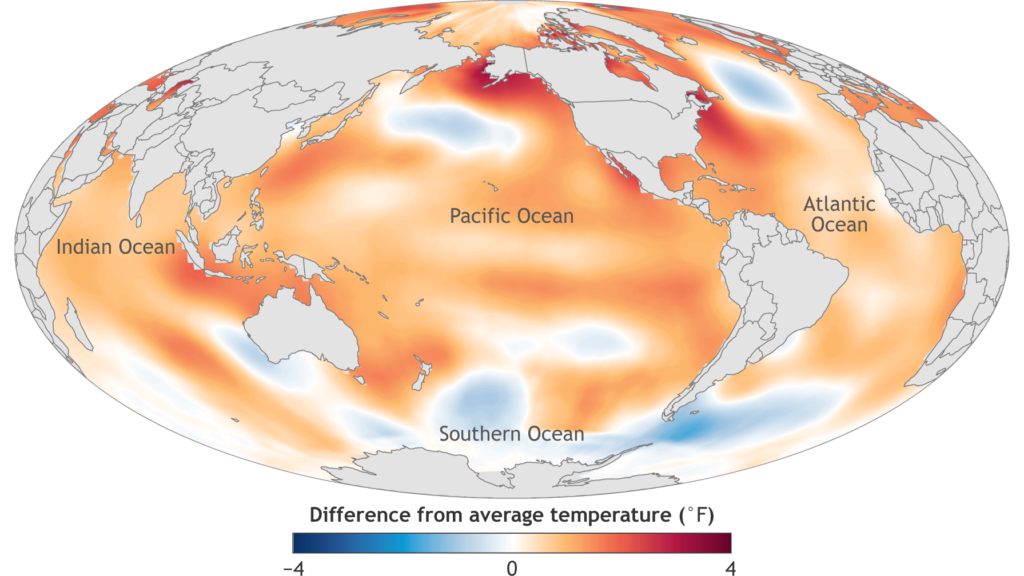

Accounting for financial constraints, the researchers calculate that natural climate change mitigation pathways could reduce emissions by 11.3 billion tons a year by 2030, or 37 percent of the reductions needed to keep global warming below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit – the central objective of the Paris climate agreement.

“That is huge potential, so if we are serious about climate change, then we are going to have to get serious about investing in nature, as well as in clean energy and clean transport,” said Mark Tercek, CEO of the environmental group The Nature Conservancy.

“We are going to have to increase food and timber production to meet the demand of a growing population, but we know we must do so in a way that addresses climate change.”

Former U.N. climate chief Christiana Figueres also noted the critical role of land use management in limiting global emissions.

“Land use is a key sector where we can both reduce emissions and absorb carbon from the atmosphere,” she said. “This new study shows how we can massively increase action on land use – in tandem with increased action on energy, transport, finance, industry and infrastructure – to put emissions on their downward trajectory by 2020.

“Natural climate solutions are vital to ensuring we achieve our ultimate objective of full decarbonization and can simultaneously boost jobs and protect communities in developed and developing countries.”

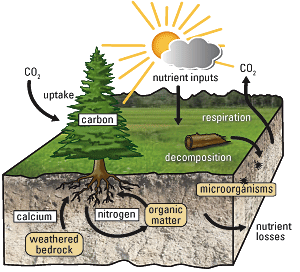

The team found that, from a cost-efficiency standpoint, trees have the greatest potential to reduce carbon emissions. Trees absorb carbon dioxide as they grow, removing it from the atmosphere. According to the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization, forests account for roughly 30.6 percent of global land area.

The three primary options for increasing tree volume – restoration, better forestry practices and avoiding forest loss – could remove 7.7 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year by 2030, equivalent to removing 1.5 billion gasoline-powered cars from the roads, according to the study.

Successful interventions depend largely on improved forestry and agricultural practices, particularly those that reduce the volume of land used by farms for livestock. Decreasing the footprint of livestock could allow for more trees to be planted – a transition that can be achieved without disrupting food production.

Refined forestry practices could also boost wood fiber production and carbon storage while maintaining biodiversity. The team found that forests in Brazil, India, China, Russia and Indonesia have the greatest potential to further reduce emissions.

The Food and Agriculture Organization estimates agricultural lands cover 11 percent of the world’s surface, and changing how these lands are farmed could produce 22 percent of necessary emissions reductions, the study finds – equal to taking 522 million cars off the road.

For example, a smarter application of chemical fertilizers could improve crop yields while also reducing emissions of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that is more than 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

“Climate change threatens the production of food staples like corn, wheat, rice and soy by as much as a quarter – but a global population of 9 billion by 2050 will need up to 50 percent more food,” said Paul Polman, CEO of the Dutch-British consumer goods company Unilever.

“Fortunately, this research shows we have a huge opportunity to reshape our food and land use systems, putting them at the heart of delivering both the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the (U.N. initiative) Sustainable Development Goals.”

While wetlands encompass less total area than forest or agricultural lands at between 4 and 6 percent of the planet’s surface, they also store the most carbon per acre and represent 14 percent of potential cost-effective reductions, according to the study. Within wetlands management, the largest opportunity for reductions is by not draining and converting peatlands.

According to estimates, peatlands hold one quarter of the carbon stored the world’s soils. Despite their valuable storage capacity, about 1.9 million acres of peatlands are lost each year, largely for palm oil cultivation. The team found that protecting these lands could enable the protection of roughly 737 million tons of carbon emissions a year by 2030, comparable to removing 145 million cars from the roads.

“This study is the first attempt to estimate systematically the amount of carbon that might be sequestered from the atmosphere by various actions in forestry and agriculture, and by the preservation of natural lands which store carbon very efficiently,” said William H. Schlesinger, a professor emeritus of biogeochemistry at Duke University and former president of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies.

“The results are provocative: first, because of the magnitude of potential carbon sequestration from nature, and second, because we need natural climate solutions in tandem with rapid fossil fuel emissions cuts to beat climate change.”

Although the findings highlight the importance of natural climate solutions, the sectors of renewable energy, clean transportation and energy efficiency receive about 30 times more funding combined.

“Just 38 out of 160 countries set specific targets for natural climate solutions at the Paris climate talks, amounting to 2 gigatonnes (2.2 gigatons) of emissions reductions,” said Justin Adams, global lands managing director at The Nature Conservancy. “To put this in context, we need 11 gigatonnes (12.1 gigatons) of reductions if we are to keep global warming in check. Managing our lands better is absolutely key to beating climate change.

“The PNAS study shows us that those responsible for the lands – governments, the forestry companies and farms, the fishermen and property developers – are just as important to achieving this as the solar, wind and electric car businesses.”

I see it all the time now- a call for “better forestry practices” to help solve the global warming problem- but they never say what that means.

Joe Zorzin

“a forester for 45 years”

Hi Joe,

Thanks for your comment. For more specifics on the basis for the gains you can look at the original article:

http://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/114/44/11645.full.pdf

From my read there are three basic things they identify. 1) Reforesting areas previously cleared and growing trees for harvest; 2) Avoided Forest Conversion ie stop deforesting; 3) Increase the amount of trees in the forest and they are specifically looking at places that are currently being grazed and instead growing more trees.

These opportunities are in the countries listed. Brazil, Russia, etc.

David, I read that original article. A really big problem is that critics of forestry and “forest policy visionaries” often have little idea how the real forestry world works- party because they make little effort to talk to guys like me. I notice a few suggestions that are not feasible and will not happen.

1. The call for low impact forestry- which implies the work should be done by small machines or horses. The implication is that such work is superior to work done by large machines. I’ve seen every type of logging work since Nixon was in the White House. Some of the very best work was done by large machines and large machines are here to stay because of the economics of logging.

2. The call for extended rotations. This is not going to happen. It’s not the length of the rotations that is important- it’s the quality of the silviculture which over the long term will give us better, more economically valuable forests and forests with higher stocking levels.

Thus, in my opinion, those calling for “improved forestry practices” don’t really know what they’re talking about. They could improve their knowledge by talking to experienced foresters.

The New England Forestry Foundation recently published our standards for Exemplary Forestry on our website. Take a look – these might be the kind of standards the authors anticipate when they talk about natural forest management. We believe it is the most effective approach to keeping carbon sequestered within forests while producing the low carbon products society needs and substituting for carbon intensive products like steel and concrete. http://newenglandforestry.org/connect/publications/forestry-guides/